The Tar Pit Trap

1. The Subject of History

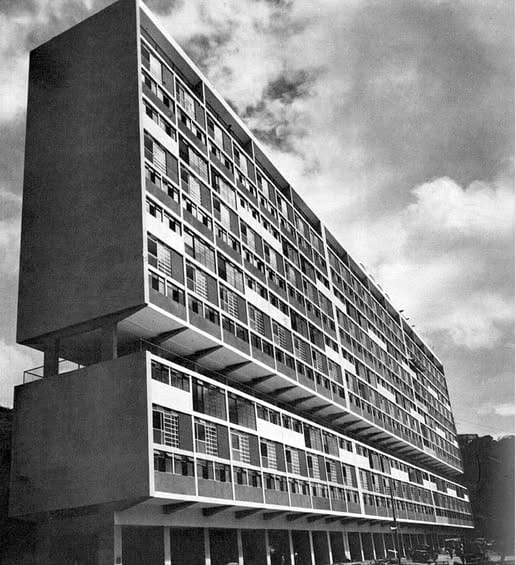

The road to the 23 de Enero climbs into a lucid dream of concrete and tropical improvisation. Coiling up the hillsides of western Caracas, the noise of the blockade fades into the golden, cinematic clarity of a memory that refuses to age. Entering the "23" is to step into a suspended moment of radical possibility, where the superblocks rise like giant sideways dominoes against the Avila range—imposing, colorful, and seemingly ready to tumble (Velasco 2015, 1). Here, the interruption of the global market appears less as an error than as a miracle. A resident stands on the roof of Block 7, overlooking the Presidential Palace with a proprietary air, as if the geometry of the city itself were a mandate to rule.

In this landscape, the atmosphere is defined by a paradoxical euphoria: a liberated territory, a vertiginous ascent through a country that briefly belonged to everyone. The people here were never merely a client class pacified by the distribution of rent; they were the active architects of their own democracy, transforming a dictatorship’s housing project into a symbol of the nation’s democratic spirit (Velasco 2015, 7–29). This was joint commitment in its purest form—a moment where the popular will seemed to gain agency over the automated logic of the market. It was the momentary realization of the civil-military union promised in the Blue Book, where the armed forces appeared finally to "wield their swords in defense of social guarantees" rather than enforcing the peace of the graveyard (Chávez 2015, 18). This initial promise remains suspended in amber: the early 2000s, when the Misiones—Barrio Adentro, Mercal—felt like a direct upload of oil rent to the social body, bypassing the rusted circuits of the traditional state.

Moving through the sectors of Monte Piedad and La Cañada reveals the physical residue of this commitment. The spaces between the high-rises are filled with the dense, organic architecture of the ranchos, creating a zone where formal and informal politics blur into a single pulse (Velasco 2015, 13). The residents carry themselves with the "sheer, intoxicating confidence" of those who once flooded Avenida Sucre to overthrow a dictator and claim the keys to their own homes (Velasco 2015, 2). They moved with the certainty that they had silenced the "old and modern despotism" (Chávez 2015, 49) and replaced it with a "living logic" of their own (Chávez 2015, 13). For a fleeting historical second, the market's hum was silenced by the roar of a multitude that believed, with heartbreaking sincerity, that they were the authors of the new Venezuela. In this moment, the "counterpoint of popular protest and electoral politics" felt like the breathing rhythm of a living organism (Velasco 2015, 8, 30–31).

The dream extends beyond the city, ascending into the Simón Planas valley. Here, aggressive green foliage swallows the grey noise of the headlines, fed by the deep aquifers of the "mysterious lands of Yaracuy" that vibrate with a fertility forgotten by the cities (Gilbert 2023, 39). Entering the El Maizal Commune means stepping into a suspended moment of agrarian sovereignty, where light hits the Sarare cornfields with a sharp, living intensity. In these fields, the "Zamoran root" of the project is visible in high contrast: the chivero and the peasant believe they have finally executed the General's mandate of "Free men and land" and "Horror to the oligarchy" (Chávez 2015, 50). The campesino stands at the edge of a disputed estate, clutching a pocket-sized blue Constitution as if it were a deed to the earth itself.

Life here moves with the rhythm of a circus that refuses to leave. Along the roadsides, cyclists pedal with frantic, whimsical dignity. Grown men hunch over tiny, bright-pink children’s bicycles, knees nearly hitting their chins as they navigate the valley floor (Gilbert 2023, 39). In this isolated pocket of the llanos, the gasoline supply chain has shattered, and the internal combustion engine has been abandoned. People adapt with surreal resilience, transforming the absence of fuel into a picaresque, day-long odyssey. The commute to the fields becomes a collective, improvised adventure. The atmosphere is defined by a hard-won serenity: a movement that describes itself as pacífica pero armada—"peaceful, but armed" (Lavelle 2013, 134). Yet, the only weapons visible are machetes for the harvest and the quiet certainty that the law is finally on their side.

In this "seemingly pro-peasant context," the occupation of land sheds the stigma of crime to become a festival of legality. The chiveros and the landless do not hide in the shadows; they step into the sun, rejecting the label of invasores and asserting with a calm logic that they are merely "recovering" the land for the state (Lavelle 2013, 146).

This defiant agency is rooted in the calloused hands of communards cultivating "war crops." Sorghum, yuca, and native beans grow explicitly to sustain life under the siege of US sanctions (Gilbert 2023, 41). The memory of this moment is specific and tactile. It smells of burning sugar cane, the sweet, acrid smoke rising as occupiers set fire to the cash crops of the oligarchy, clearing the "latifundio uses" to make way for the war crops of food sovereignty (Lavelle 2013, 148). The corn harvest functions as a defense measure, transcending simple agriculture. A spiritual surplus drives this labor, making the hard work of the harvest feel like an act of triumphant creation.

This fragile autonomy extends beyond the commune into the vast territory of Torres. Driving the "twisty road" into the deep country leaves the cynical mechanics of the global market behind. The traveler enters a landscape that seems to belong entirely to the people traveling through it for a brief, delirious season. The terrain itself is "disarmingly romantic," a cinematic sweep of "scorched desert valleys" giving way to "lush mountains" that hold the sun's heat in a benevolent embrace (Hetland 2023, 74; 88).

In this radiant hour of the Bolivarian process, the road is lined with the "ramshackle stands" of the chiveros. These goat farmers sell suero and cheese, their voices amplified by the acoustics of a new state after a century of silence (Hetland 2023, 67). Historically derided by the cattle-ranching godarria oligarchy as relics, these men and women have become the territory's protagonists. They stand elevated above the land barons who once ruled these hills. Sunlight hits the dust on the road to Curarigua until it resembles gold dust, a visual rhyme with the oil rent finally diverted into the hands of the poor. A moment of pure clarity reveals that the land is theirs.

Inside the Casa de Cultura courtyard, sheltered from the blistering sun, the assembly celebrates this new ownership (Hetland 2023, 88). The atmosphere carries the intimacy of a neighborhood gathering where the state automaton must sit and listen. Zoila Vásquez, secretary of the Local Planning Council, argues against purchasing a new ambulance. She insists instead on the humble, practical necessity of repairing tires for the existing fleet. She commands the budget, bypassing the need to beg a distant minister for favors (Hetland 2023, 92).

The joyful memory remains specific and material: the shock of the "100 percent budgetary transfer" (Hetland 2023, 65). This was the mechanics of the original society in practice (Chávez 2015, 61), a "supportive way of life" where the people "consult themselves on the means to satisfy their desires" instead of waiting for the state to dictate them. The communal body realizes they can override the engineer's technical logic with the peasant's lived logic. The assembly votes with Zoila. They ignore state official Sandry Gil's warning to "think about the future," and relief washes over the room (Hetland 2023, 91). It feels like a permanent victory, a scenic memory of a time when the budget was real, the currency held value, and the chivero believed he had finally inherited the earth. This dream tasted of the raw, intoxicating reality of power before the market's gravity returned to crush it.

It feels like a dream of autonomy. The bronze bust of Chávez keeps stern vigil over the caney, and the air thickens with the mystique of a people who believe they have seized the means of their own survival (Gilbert 2023, 42). Standing in the high corn, the market automaton seems permanently exorcised, replaced by the sheer, stubborn vitality of a people who have learned to eat, breathe, and live on their own terms. But this agrarian idyll is a fragility, a joyful memory constructed on the edge of an abyss. The joyful memory is haunted by the silence of the sicariato, the hired assassins moving like ghosts through the high grass (Lavelle 2013, 144). The campesino sleeps with one eye open, knowing that the National Guard—the supposed defenders of this new reality—might arrive only to take photographs and vanish into the night. The affective surplus of the commune masks a brutal material deficit: members dying from the lack of medicine, and the silent, grinding attrition of the blockade that turns every harvest into an act of defiance against a global system designed to crush them (Gilbert 2023, 120).

The road from the llanos into the urban centers of the mid-2000s followed the logic of a 'refracted hegemony,' where even the old political class was compelled to mimic the language of the poor (Hetland 2023, 10). This was more than a policy shift; it was a hallucinatory moment where the Right was forced to play by the Left's rules, turning the municipal budget into a binding script for the socially necessary abstraction of hope (Hetland 2023, 110, 258). In the "First Socialist City" of Torres, the transition from clientelism to radical agency appeared as a lucid interval. The participatory budget—giving citizens binding control over 100 percent of investment funds—functioned as a biological pulse, a moment where 25 percent of the population moved in a synchronized delirium of self-governance (Hetland 2023, 65, 82). It felt like a scenic road trip through a country that had finally solved the riddle of the state, before the "hyperdependence on oil" turned the dream into a terminal crisis (Hetland 2023, 60).

As the oil price collapsed after 2013, the high-resolution lucidity of this dream began to buffer. The hyperinflationary spiral of the currency accelerated until it outpaced the biological survival time of the worker. The Maduro diet emerged here not merely as scarcity, but as a caloric deficit where the minimum wage collapsed alongside the bolívar, turning the daily life of the citizen into a frantic struggle against the theta decay of their own labor power. The euphoria of the early Misiones was replaced by the silence of the stomach, as the biological clock of the peasant clashed with the hyperinflationary clock of the state.

The civil-military alliance, designed to be the "people in arms" (Chávez 2015, 26), inverted its function. The Zamoran federal state (Chávez 2015, 67) did not emerge; instead, the state apparatus was captured by a caste that treated the exchange rate as a resource to be mined. Rather than smashing the bourgeois state, the revolution bloated the command structure to secure the loyalty of its praetorian guard. By 2019, the military leadership had ballooned to "as many as 2,000 admirals and generals"—a figure representing "twice the top brass as the U.S. military" and ten times the number existing at the start of the Bolivarian presidency (Dayton 2019, 32). This expansion constituted a bureaucratic metastasis, with officers appointed to public offices and the state oil company, PDVSA, based on party loyalty. The officer corps became a caste defined by privileged access to the arbitrage mechanisms of a dying economy.

Under the cover of this rank inflation, the "Cartel of the Suns" emerged. Viewed through the lens of a hostile security audit, this appears simply as "criminality." However, a materialist autopsy reveals a desperate survival strategy: the transformation of the state’s logistical arteries into channels for illicit finance to bypass the blockade. The officer corps ceased to be the guardians of the initial promise and became the operators of a liquidation committee, trading the sovereign capacity of the nation for the liquidity required to govern (Dayton 2019, 32–33). The plural subject on the roof of Block 7 was left behind as unwaged data-labor, while the state apparatus dissolved into a decentralized network of para-state enforcers. The dream of the 23 de Enero did not die; it was simply sold for parts.

2. Broken Protocol

To comprehend the paralysis, one must strip away the political theater and examine the commodity itself. The task is to descend from the headlines into the geological pit where value is created—or, in this case, where it rots. The American capture strategy is blinded by a fetishistic misunderstanding of its target, viewing the Venezuelan reserve as a static loot box containing 303 billion barrels of liquid value. But Venezuela is no bank vault; it is a distressed asset defined by a broken metabolic protocol. This error stems from a "mechanistic" worldview that treats economic assets as reversible, timeless stores of value, ignoring the "entropic" reality that quality change is irrevocable (Georgescu-Roegen 1971, 1-2). Far from a negation of capitalism, the Bolivarian experiment functioned as a glitch in the commodity boom, a temporary anomaly that allowed the state to redistribute surplus without altering the "underlying class structure" or the "model of accumulation" (Webber 2017, 11).

The Paper Tiger

The figure of 303 billion barrels—the "proved reserves"—stands as a monument to Fernando Coronil's "Magical State," a spell that "seizes its subjects by inducing a condition or state of being receptive to its illusions" (Coronil 1997, 5).

This statistic masks the fatal distinction between geological existence and economic realizability. The "Magna Reserva" certified "oil in place" even as the capacity to transform it collapsed (Monaldi 2020, 16). The regime used the reserve to veil the infrastructure's true "disposition" (Easterling 2014, 21). Without a functioning apparatus, the reserve remains merely nature. The US has captured a map of potential wealth, distinct from realized capital (Monaldi 2020, 5).

The state operates on a Nominal Valuation ($V_{\mathrm{nom}}$), assuming all booked reserves are commodifiable at current market prices:

$$V_{\mathrm{nom}} = R_{\mathrm{total}} \times P_{\mathrm{global}}$$

But this abundance is a valuation dependent on a vanished state of the global market. The proved reserve is a fiction maintained by the rentier-capitalist state, which intensified the economy's addiction to the export signal. Under the Bolivarian process, the oil share of total export value did not decline; it rose from 68.7 percent in 1998 to 96 percent in recent years (Webber 2017, 41).

When the protocol of extraction is severed, the 303 billion barrels revert from capital back into nature. An Extra-Heavy Crude asset demands modeling as a dynamic process, distinct from a static loot box. To determine the Realizable Value ($V_{\mathrm{real}}$), we must integrate the flow rate $q(t)$, constrained by the physical laws of entropy.

Physics of Decay

The extraction rate, $q(t)$, stands as a physical verdict—a function of infrastructure health and fluid viscosity—not a financial choice:

$$q(t) = \kappa \cdot \frac{I(t)}{\mu} \cdot \Delta P$$

In this formalism, extraction $q(t)$ is the offspring of geology and neglect. Flow is driven by reservoir pressure ($\Delta P$) and permeability ($\kappa$), but strictly governed by the ratio of infrastructure health to fluid resistance. $I(t)$ represents Infrastructure Integrity—the "Low Entropy Fund." This variable opposes $\mu$, the extreme viscosity of the extra-heavy crude. If infrastructure ($I(t)$) degrades faster than viscosity ($\mu$) is managed, the flow rate approaches zero regardless of reservoir pressure.

The "Flow Constraint" is historically verifiable. The CEPR analysis isolates a specific "kink" in the production curve following the August 2017 sanctions. Prior to this intervention, production was declining in tandem with Colombian output; immediately following the sanctions, the rate of decline accelerated to more than three times the previous trend (Weisbrot and Sachs 2019, 8). This acceleration was not a geological accident but a financial asphyxiation, stripping the system of the credit required to maintain the infrastructure. In this context, the sanctions functioned as a "switch" (Easterling 2014, 17), a binary active form that went beyond pausing the market to irreversibly alter the chemistry of the "zone" itself.

Here, $I(t)$ models the infrastructure as a dying body, contrasting with the static asset of financial models. The negative exponential term $e^{-\lambda t}$ is the mathematical signature of entropy, quantifying the "half-life" of industrial capital in the tropics. It represents the relentless degradation of steel and electronics when exposed to heat, humidity, and neglect.

$$I(t) = I_0 \cdot e^{-\lambda t} + \int\limits_{0}^{t} \mathrm{CAPEX}(\tau) \cdot e^{-\lambda(t-\tau)} , d\tau$$

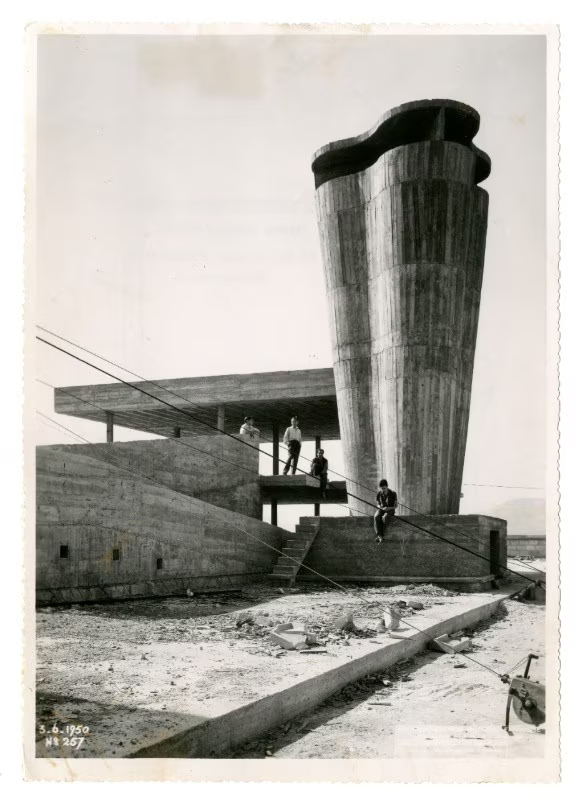

The first term, $I_0 \cdot e^{-\lambda t}$, dictates that without intervention, the initial infrastructure ($I_0$) decays toward zero at a rate determined by $\lambda$ (corrosion, wear, and obsolescence). The only force capable of arresting this decline is the second term: the integral of $\mathrm{CAPEX}(\tau)$. This represents the cumulative "metabolic feeding" of the system—the continuous injection of parts, lubricants, and labor. The equation proves that maintenance represents a thermodynamic necessity, far more than an optional cost; without this constant financial injection to counteract the drag of nature, the system essentially digests itself. The infrastructure must continuously "suck low entropy" from its environment to arrest its own degradation, a biological imperative that the financial model fails to account for (Georgescu-Roegen 1971, 10-11).

The Realizable Value Integral

The "Realizable Value" ($V_{\mathrm{real}}$) is a temporal integral—a summation of future flows discounted by risk—distinct from a static number found in a bank account. We must integrate the Flow $q(t)$ over time, moving beyond the simple counting of Stock in the ground. This shift reveals that value is generated only through motion.

The equation splits the problem into two competing timelines: the revenue generated by the flow (minus the cost of diluents) and the cost of the capital required to sustain that flow.

$$

V_{\mathrm{real}} = \int\limits_{0}^{n} \left( [Q(t) \cdot \pi_{\mathrm{net}}] - I_{\mathrm{capex}}(t) \right) e^{-rt} , dt

$$

The first integral represents the potential wealth: the daily extraction rate multiplied by the profit margin, discounted by time ($e^{-rt}$). The second integral represents the "entropy tax": the continuous CAPEX required to keep the machine running. If the cost of fighting entropy exceeds the revenue from the flow, the value turns negative.

This operation is bound by a hard physical limit, the Constraint:

$$

\int\limits_{0}^{\infty} q(t) , dt \le R_{\mathrm{total}} \times F_{\mathrm{rec}}

$$

Here, the Recovery Factor ($F_{\mathrm{rec}}$) acts as a geological censor. In the Orinoco Belt, without advanced Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR), this factor is historically low (approx. 20%). This physically caps the "infinite" reserve before extraction even begins. The formalism proves the Tar Pit conclusion: if $\mathrm{CAPEX} \to 0$ (due to sanctions or theft), then infrastructure integrity $I(t) \to 0$, causing the flow $q(t)$ to halt. The Realizable Value approaches zero even if the Stock ($R_{\mathrm{total}}$) remains infinite. The 303 billion barrels are thus revealed as an "arithmomorphic fiction" (Georgescu-Roegen 1971, 44)—a number that exists on paper but cannot exist in the economy because the cost of the flow rate has not been paid.

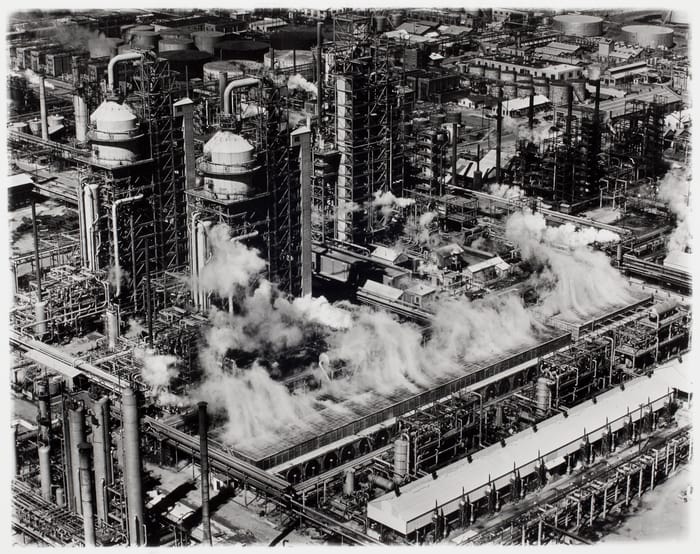

Chemical Siege

Far from a reservoir of liquid capital, the Orinoco Heavy Oil Belt exists as a geological singularity defined by extreme viscosity. It contains extra-heavy bitumen (8–14° API) that requires "energy intensification"—imported diluents—to flow. This system operates on a fragile autocatalytic loop: diluents permit flow, flow generates cash, and cash purchases maintenance and diluents (DeLanda 1997, 79).

Extraction from the Orinoco Belt is a manufacturing process; the crude is physically immobilized (Monaldi 2020, 2). It requires upgraders and diluents to become value, implying that the reserve does not become a commodity without a functioning industrial upgrader. The Processing State ($\delta_{\mathrm{proc}}$) acts as a binary variable: it is 1 if and only if upgraders are functional and diluents are present. If the supply chain is severed, $\delta_{\mathrm{proc}} \to 0$, driving realizable value to zero.

The geology imposes a high "sunken cost" barrier: the capital required to mobilize this sludge is "immobilized" in the territory before a single dollar of profit can be realized (Monaldi 2020, 4). The US is seizing the rusted cage of this trap: a vast array of fixed capital that has been stripped of its variable component.

Recall the Flow Constraint ($q(t) \propto 1/\mu$): as viscosity rises, flow approaches zero. The critical vulnerability is that $\mu$ is a synthetic variable dependent on imported chemistry. To achieve a viable flow rate, the operator must reduce the viscosity of the heavy crude ($\mu_{\mathrm{heavy}}$) by blending it with a diluent. We define the effective viscosity ($\mu_{\mathrm{mix}}$) using the Logarithmic Mixing Rule:

$$ \ln(\mu_{\mathrm{mix}}) = x_{\mathrm{dil}} \cdot \ln(\mu_{\mathrm{naphtha}}) + (1 - x_{\mathrm{dil}}) \cdot \ln(\mu_{\mathrm{heavy}}) $$

Here, $\mu_{\mathrm{heavy}}$ is the natural state of the bitumen (near-solid), and $\mu_{\mathrm{naphtha}}$ is the low viscosity of the imported diluent. The variable $x_{\mathrm{dil}}$ (the Diluent Ratio) is the lever of sovereignty.

This formalism reveals the system's extreme sensitivity to the blockade. Because the relationship is logarithmic, a linear reduction in the diluent supply ($x_{\mathrm{dil}}$) results in an exponential increase in viscosity ($\mu_{\mathrm{mix}}$). If the supply chain for naphtha is severed, $\mu_{\mathrm{mix}}$ reverts instantly to $\mu_{\mathrm{heavy}}$. The substance in the pipes ceases to behave like a fluid and begins to behave like a plug.

The blockade, therefore, does not merely "stop trade"; it physically alters the phase-state of the asset. When the catalytic input (diluents) was removed, the material reality of the Belt reasserted itself. The oil did not just lose value; it underwent a phase transition from a fluid market commodity to a solid geological burden. The US has not captured a well; they have captured a tar-pit where the "mineralization" of the state infrastructure is now irreversible (DeLanda 1997, 27). The barrel does not exist in the ground; it exists only at the end of an industrial chain that has been severed.

The revolution failed to sovereignize this processing capacity. Instead, industrial manufacturing collapsed, falling from 17 percent of export value in 2000 to 13 percent in 2013 (Webber 2017, 41). The magical state believed it could simply capture the rent from the ground, ignoring the fragile industrial web that sustained the alchemy. When the machinery stops, the "natural body" of the nation (Coronil 1997, 4) ceases to be a source of life and becomes a toxic swamp.

The analysis indicates the precise cause of failure: the severance of the diluent arteries. Washington explicitly instructed foreign trading houses to halt the delivery of refined products essential for diluting Venezuela’s heavy crude (Weisbrot and Sachs 2019, 11). By severing the supply of naphtha, the US effectively altered the phase-state of the reserve from a liquid asset into a solid liability.

We can express this as a Diluent Cost Model ($C_{\mathrm{blend}}$), which quantifies the price of making the sludge flow:

$$C_{\mathrm{blend}} = R_{\mathrm{dil}} \times P_{\mathrm{naphtha}} + C_{\mathrm{trans}\_\mathrm{dil}}$$

Here, $R_{\mathrm{dil}}$ is the "Diluent Ratio" (often 30–50%), $P_{\mathrm{naphtha}}$ represents the global market price of the solvent, and $C_{\mathrm{trans}\_\mathrm{dil}}$ accounts for the logistical cost of importing this solvent. Absent the continuous injection of light crude, the Venezuelan reserve ceases to be a liquid asset, hardening into a solid liability.

If upgraders are broken, the output is not "Synthetic Crude" but "Merey 16" or worse. We must therefore apply a Quality Discount to the revenue. The realized price is the global benchmark minus penalties and the cost of the diluent:

$$P_{\mathrm{realized}} = P_{\mathrm{brent}} - D_{\mathrm{qual}} - C_{\mathrm{blend}}$$

The term $P_{\mathrm{brent}}$ is the global benchmark, but the Venezuelan state never sees this number. From it, we must subtract the Quality Discount ($D_{\mathrm{qual}}$), which penalizes the crude for its high sulfur and heavy metal content, and the Blending Cost ($C_{\mathrm{blend}}$), which is the price of the solvent itself. This equation demonstrates that as the infrastructure fails and the cost of evading sanctions rises, the realized price ($P_{\mathrm{realized}}$) can turn negative. The blockade reverses the modernization process, turning the sophisticated "Petro-State" back into a primitive extractor unable to master its own terrain. Without the specific "coking" refineries in the US Gulf Coast, the Venezuelan reserve is chemically incompatible with the global market.

Financial Kill-Switch

The collapse was sealed by a "financial kill-switch." Even as the state attempted to manage the crisis, the August 2017 sanctions legally prohibited the government from borrowing in US financial markets, which effectively prevented the restructuring of foreign debt (Weisbrot and Sachs 2019, 7). Since any debt restructuring requires the issuance of new bonds—a "new" borrowing event under US law—the sanctions made a negotiated exit from default impossible. This trapped the state in a sovereign liquidity crisis where it could neither pay nor renegotiate, ensuring that the CAPEX Hole would only widen as foreign exchange earnings plummeted.

The logic of the asset is defined by the "obsolescing bargain" of the rentier state. The investment cycle of the Apertura (1990s) deployed billions in fixed capital—upgraders, terminals, pipelines—under the assumption of contractual stability (Monaldi 2020, 6–8). However, as prices rose, the state enacted a "regulatory expropriation," maximizing the "government-take" through windfall taxes and forced migration to Joint Ventures (Monaldi 2020, 11–12). This severed the link between profit and reinvestment. The "Operating Service Agreements" that once sustained production in mature fields were voided, and the foreign capital fled, leaving the machinery to be consumed by the entropy of the tropical climate. The heist logic fails to account for this temporal decay: the US assumes it is capturing the asset at $t=0$ (investment phase), when in reality it is capturing it at $t=\mathrm{final}$ (decomposition phase).

The CAPEX Singularity

The American strategy presumes the seizure of a cash cow but has captured a debt trap. The "redistribution" of the boom years was funded by a "hemorrhaging of highly subsidized foreign currency" (Webber 2017, 41) and "capital flight" estimated at $150 billion (Webber 2017, 43). This value was siphoned into offshore accounts rather than invested in maintenance.

The gap between the state's projections and the material reality of production is quantifiable. The "Plan Siembra Petrolera" (Oil Sowing Plan) projected a production target of 6.0 million barrels per day by 2019; the reality was a collapse to 1.5 million (Monaldi 2020, 33). This deviation represents the CAPEX Hole—the cumulative deficit of non-investment. Restoring production requires recovering from a decade of financial neglect. Even maintaining flat production requires a "Red Queen" race of ongoing maintenance due to "dilapidated drilling infrastructure" and the rapid decline rates of mature fields (Monaldi 2020, 3). The US is not acquiring a cash cow; it is acquiring a liability where the marginal cost of the next barrel includes the reconstruction of the industry.

The looting narrative assumes a "turn-key" operation, but we must model the Restoration CAPEX ($K_{\mathrm{res}}$) required to reverse the entropy of the "dilapidated drilling infrastructure." Instead of re-defining the decay, we must invert the equation to solve for the cost. We ask: what is the price to reverse the entropy that has already occurred?

We define the "Restoration Gap" ($K_{\mathrm{res}}$) as the integral of the difference between the required infrastructure and the current ruins:

$$

K_{\mathrm{res}} = \int\limits_{t_{\mathrm{now}}}^{t_{\mathrm{target}}} \left( \frac{Q_{\mathrm{target}} \cdot \mu}{\kappa \cdot \Delta P} - I(t_{\mathrm{now}}) \right) \cdot e^{\lambda \tau} , d\tau

$$

This formalism mathematically ties the "Flow Constraint" to the "Financial Cost." To achieve a target flow rate ($Q_{\mathrm{target}}$), the operator must pay for the gap between the necessary physics ($\frac{Q \cdot \mu}{\kappa \cdot \Delta P}$) and the actual broken reality ($I(t_{\mathrm{now}})$). The term $e^{\lambda \tau}$ acts as a compound interest rate on neglect: the longer the system has rotted, the exponentially higher the cost to fix it.

Since 2013, the "maintenance function" has been flatlined. To return to a production level of 2 million bpd, the operator cannot simply flip a switch; they must pay a lump sum Restoration Cost estimated at $115 billion. The US has acquired the bill for a century of magical thinking.

The Geopolitics of Exclusion

We can now construct the final Net Present Value (NPV) equation for the US operation to determine its economic rationality. First, we isolate the Net Margin per Barrel ($\pi_{\mathrm{net}}$), which represents the actual cash generated by each unit of oil before capital costs:

$$

\pi_{\mathrm{net}} = P_{\mathrm{mkt}} - C_{\mathrm{lift}} - C_{\mathrm{blend}} - C_{\mathrm{sec}}

$$

The Market Price ($P_{\mathrm{mkt}}$) is reduced by Lifting Costs ($C_{\mathrm{lift}}$), Blending Costs ($C_{\mathrm{blend}}$), and the Security Cost ($C_{\mathrm{sec}}$). This security cost includes militarized shipping subsidies—US Navy escorts—transferring risk from private majors to the taxpayer. The operation is economically irrational for the state.

We then plug this margin into the master equation. This formula now integrates the physical decay ($I_{\mathrm{capex}}$) with the financial reality, balancing the meager flow of profit against the massive weight of debt and risk:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{NPV}_{\mathrm{US}} = \sum_{t=0}^{n} & \frac{[Q(t) \cdot \pi_{\mathrm{net}}] - I_{\mathrm{capex}}(t)}{(1+r+\rho)^t} \\

& - L_{\mathrm{inherited}}

\end{aligned}

$$

The denominator discounts future cash flows with a rate inflated by the Risk Premium ($\rho$) of insurgency. Finally, the term $L_{\mathrm{inherited}}$ represents the external debt and arbitration claims exceeding $191 billion that the new owner must assume (Tooze 2026).

The acquirer inherits external debt and arbitration claims ($L_{\mathrm{inherited}}$) exceeding $191 billion. With a massive Restoration Cost ($K_{\mathrm{res}}$), high blending costs ($C_{\mathrm{blend}}$), and an extreme Risk Premium ($\rho$) due to active insurgency, the result is mathematically unavoidable:

$$

\mathrm{NPV}_{\mathrm{US}} \ll 0

$$

The operation is economically irrational as a profit-seeking venture (Accumulation). Therefore, the operation must be solved for a different variable: Geopolitical Denial. The utility function is not Profit ($U_{\pi}$), but Exclusion ($U_{\mathrm{ex}}$):

$$

U_{\mathrm{ex}} = (\mathrm{Cost}_{\mathrm{China}} \to \infty) + (\mathrm{Security}_{\mathrm{China}} \to 0)

$$

The US is willing to absorb a negative financial NPV because the goal is strategic denial—removing the asset from the rival's ledger, regardless of the cost to its own (Platias 2026). The formal logic confirms the text's conclusion: The US functions as an agent of entropy rather than an extractor.

3. Imperialism as Illicit Weakening

This text dissects a denial-of-service attack executed in the dark. Distinct from the physical absorption of crude—the tanks are already full—the American objective is not consumption but deletion: the calculated removal of a strategic asset from the adversary’s supply chain. We are witnessing a renegade operation in real-time, executing the 'Donroe Doctrine'—a sphere of influence enforced through demonstrative violence (Tooze 2026). It is a diagnostic of illicit weakening: the deliberate transformation of a resource node into a dead zone, ensuring the rival’s energy security matrix collapses into a series of unfulfilled liabilities while the world looks the other way.

The Energy Independence Illusion

The Shale Revolution was a high-stakes gamble with a steep expiration date. Far from a stable plateau, US energy independence represents a desperate sprint against the Decline Rate ($\lambda$).

We define the Shale Production Function $P_{\mathrm{shale}}(t)$ using the Hyperbolic Decline Curve typical of fracked wells. Unlike conventional reservoirs that decline gently, shale wells behave like bursts of adrenaline:

$$P_{\mathrm{shale}}(t) = q_i(1 + b D_i t)^{-1/b}$$

Here, $q_i$ is the initial production burst, $D_i$ is the steep initial decline rate, and $b$ controls the curvature of the crash. The physics of fracking dictate that these wells decline by approximately 70% in the first year. This creates another Red Queen constraint: to maintain flat production ($dP/dt = 0$), the industry must run faster and faster, drilling exponentially more wells just to stay in the same place. The illusion of independence collapses at the mathematical point where the capital cost of this treadmill ($\mathrm{CAPEX}_{\mathrm{maintain}}$) exceeds the revenue generated.

This decaying production curve is colliding with a new, ravenous variable: the exponential energy demand of the AI sector. The energy demand follows a geometric progression driven by the scaling laws of Large Language Models:

$$E_{\mathrm{total}}(t) = E_{\mathrm{base}} + \alpha \cdot e^{rt}$$

In this function, $E_{\mathrm{base}}$ represents the legacy grid load (lights, HVAC, industry), which is relatively stable. The disruption comes from the second term, where $\alpha$ is the baseline compute load and $r$ is the compounding growth rate of data centers. While shale production struggles against gravity, AI demand is achieving escape velocity.

The structural crisis occurs when these two lines cross—when the Domestic Deficit ($\Delta E$) becomes positive:

$$\Delta E(t) = E_{\mathrm{total}}(t) - P_{\mathrm{shale}}(t) > 0$$

Because $P_{\mathrm{shale}}$ is asymptotically decaying (high decline rate) and $E_{\mathrm{total}}$ is exponentially exploding, the US is mathematically destined to move from Energy Independence back to Dependency. This deficit necessitates the capture of external, politically controllable energy to feed the processors.

Logic of Strategic Denial

The US need not consume Venezuelan oil; it must simply ensure China cannot. The machine has no hunger; it possesses only a jealousy that mandates the rival’s starvation. This requires shifting the logic from Profit Maximization to Strategic Denial.

We redefine the US Utility Function ($U_{\mathrm{US}}$). In a standard market, utility is based on acquiring volume ($V_{\mathrm{oil}}$). In the renegade scenario, utility is based on the Deprivation of the Rival:

$$U_{\mathrm{US}} = (1-\delta) \cdot V_{\mathrm{domestic}} - \gamma \cdot V_{\mathrm{China}}$$

Here, $\gamma$ (The Hostility Coefficient) represents the geopolitical weight of hurting the adversary. Even if the Cost of Extraction ($C_{\mathrm{ext}}$) in Venezuela is too high for the US to make a profit ($\mathrm{NPV} < 0$), the operation is "rational" if it successfully drives $V_{\mathrm{China}} \to 0$.

The capture of Venezuela concerns enforcing a limit on the adversary’s variable $V_{\mathrm{China}}$, with no intent to feed the US machine—which cannot process the heavy crude profitably. It is a calculation of negative utility: ensuring the rival's energy matrix remains empty.

The operation is a liquidation protocol disguised as a liberation. By severing the 300,000-barrel-per-day tether to Beijing—and instructing refiners and trading houses globally to cut all dealings or face the same predatory force—the US is mapping violence onto the "global seams" of trade (Cowen 2014, 8, 89). The renegade state doesn't need to win the market; it only needs to break the connection. Total exclusion is the only security. To allow even a single drop to anchor a rival currency bloc is to permit a "disruption" to the life of American trade—and in this new map of the world, disruption is treated as an act of war (Cowen 2014, 3, 12).

Renegade Protocol

The 'Trump Corollary' defines the Western Hemisphere as an exclusive zone where external powers are "strategic threats to be rolled back" (Platias 2026). This is the nineteenth century returning with a scalpel: gunboat diplomacy updated for the era of information operations. We are drifting back to a brutal logic of power where the Monroe Doctrine is a strategic choice to enforce a backyard of silence.

The US acts as a renegade vandal, unmoored from the juridical constraints of the post-war order—a shift Tooze describes as the transition to 'feckless reality TV' imperialism (Tooze 2026). It need not consume the oil, only ensure the adversary inherits nothing but corroded infrastructure and toxic debt. This is the "Deadly Life of Logistics": a geography of imperial force where the supply chain morphs from a pipeline into a noose (Cowen 2014, 9).

The renegade protocol operates with a clinically indifferent necropolitics. The deprivation of foreign exchange did not merely rust the pipes; it induced a 31 percent increase in general mortality between 2017 and 2018, corresponding to more than 40,000 excess deaths in a single year (Weisbrot and Sachs 2019, 15). By 2018, over 300,000 people were at immediate risk due to a lack of medicines, including 80,000 HIV patients denied antiretroviral treatment (Weisbrot and Sachs 2019, 15). This statistical excess constitutes "collective punishment" under the Geneva and Hague conventions (Weisbrot and Sachs 2019, 18).

Political Vacuum

The capture of Maduro reveals the ultimate expiration of the "Refracted Hegemony" protocol. Between 2005 and 2013, the Left’s intellectual leadership was so total that the opposition was forced to operate on its terrain (Hetland 2023, 117–144, 258). However, the current impasse results from the collapse of the $(\mathrm{Oil} \multimap \mathrm{Hegemony})$ function. When the material basis for class compromise evaporated, the state was left with only the "Pasivización" of the masses (Hetland 2023, 31, 269).

Unlike the "active revolution in Bolivia," the Venezuelan trajectory was 'Involutionary'—a top-down disintegration where the ruling class failed to sustain the very Popular Power it had manufactured as its shield (Hetland 2023, 19, 27–28, 147). The US heist is thus a play for a machine that has already lost its ghost; they are seizing a Refractory asset that no longer generates the moral unity required to pump a single barrel of profitable crude (Hetland 2023, 28).

4. Scavenger

The American strategy is blind to the "subcontracting" of violence that now defines the Venezuelan interior (Dayton 2019, 31). The state has devolved power to armed non-state actors—including Colombian guerrillas and colectivos—who now perform state functions such as taxation and local governance (Dayton 2019, 35). These groups control up to 10 percent of all urban towns and have forcibly seized mining operations (Dayton 2019, 34). Even the removal of the Administrator does not clear the board; it leaves the US to confront a decentralized network of 1.6 million militia members who preside over entire neighborhoods (Dayton 2019, 32-33). The asset is not just distressed—it is occupied by an embedded insurgency with a "vested interest" in the regime's survival (Dayton 2019, 31).

Seizing the state is a desperate move against a system that has already begun to rot. This collapse is a structural feature of the "carbon democracy" paradox. Mitchell (2011, 39) defines "sabotage" as the "conscientious withdrawal of efficiency" by those who control the narrow channels of energy flow, rather than kinetic violence. By extracting the figurehead, the US State completes its transition from Market Maker to Arbitrage-Extractor.

As Mitchell argues, the industry's primary imperative is the 'production of scarcity' to maintain value; in this context, the maneuver functions as a desperate attempt to floor the price of a stranded asset. To "keep the oil" is to inherit the entropy of a system where the cost of restoration exceeds $100 billion, a figure that renders the "prize" a mathematical impossibility (Rystad Energy 2026).

Dayton’s diagnostic confirms the US has captured a "geopolitical dead zone," a far cry from a prize. Uprooting the paramilitary groups that have "sworn to start insurgencies if Chavismo is removed" will pose a significant challenge for any post-Maduro government (Dayton 2019, 35). The Insurgency Tax renders the "oil strands" unprofitable; the cost of taking back territories controlled by these groups, coupled with the risk of 5,000 Russian Igla-S portable anti-air missile systems entering the black market, transforms the heist into a permanent security liability (Dayton 2019, 35).

Operating under the logic of Sovereign $\to$ Liquidation, the US functions as a Vulture Capitalist, never a builder. There is no intent to "democratize." The infrastructure space has been marked for subtraction (Easterling 2014, 205). The extraction is no longer about the flow of crude, but the liquidation of Citgo, the foreclosure of gold reserves, and the enforcement of debt repayments. This is the geopolitics of planned obsolescence: the hardware has been designed with software locks and proprietary connectors that, once severed, ensure the asset's productive value decays rapidly.

The "Campist" defense of the state remains trapped in a destructive loop, demanding that citizens sacrifice themselves to maintain the zombie sovereignty of a terminal nation-state (Thom 1975, 126). This defense ignores the crushing weight of ecological debt. The landscape is a balance sheet where the productive value of the hardware is finally outweighed by the negative value of the climate collapse it accelerated. The Campist clings to the image of the factory, refusing to see that the floodwaters have already risen past the intake valves.

Amidst the wreckage, the scavenger socialist emerges as the only viable form of life.

This subject is the mature evolution of the "occupier" who first emerged in the gaps of the early Bolivarian process. The "politics of production" that once drove peasants to burn sugar cane has now mutated into a survival mechanism against the state itself. The "technically illegal" agency that defined those early land seizures has become the standard operating procedure for a population that can no longer wait for permission from a paralyzed bureaucracy (Lavelle 2013, 148).

The scavenger of 2026 inherits the siege mentality of 2005, but the stakes have shifted. The "peaceful but armed" doctrine has hardened into a permanent mechanism of asymmetric defense against the very government that claims to represent them (Lavelle 2013, 134). The structural antagonism identified by Lavelle has generalized across the entire social body (Lavelle 2013, 147). The suspicion that the red t-shirt of the bureaucrat conceals the mentality of the old regime is no longer a paranoia; it is the baseline reality of the survival economy.

In the El Maizal commune, the cyclist pedals through the wasteland, navigator of the void. He does not check the exchange rate of the Bolívar; he has already stepped outside of market time. The currency is a ghost, so he trades in the tangible: a kilo of corn, a repaired motor, a strip of copper scavenged from a redundant substation. This is a meshwork of nobodies who have realized that the state, far from a protector, operates as a "mechanism of obstruction" (Gilbert 2023, 42). By shattering the state apparatus, the sanctions paradoxically strengthened this network, forcing the population into a hyper-localized mode of survival (DeLanda 1997, 64-65) that the US bureaucracy cannot govern.

While the geopolitical titans wrestle for control of the broken machine, the resistance has already moved on. In the communes, the "emergency brake" has been pulled (Gilbert 2023, 183). The US has kidnapped the CEO of a bankrupt firm, unaware that the workers have already seized the only assets that remain solvent: the land, the seed and the rifle. The flag may rise over Miraflores, but the ties between paramilitaries and security forces "will not disintegrate quickly or entirely" (Dayton 2019, 35). The liquidation is complete, and in the silence of the abandoned fields, the survival has just begun.

References

Chávez, Hugo. [1991] 2015. The Blue Book. Prologue by Nicolás Maduro. Caracas: Ministry of the People's Power for Communication and Information.

Coronil, Fernando. 1997. The Magical State: Nature, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cowen, Deborah. 2014. The Deadly Life of Logistics: Mapping Violence in Global Trade. University of Minnesota Press.

Dayton, Ross. 2019. "Maduro’s Revolutionary Guards: The Rise of Paramilitarism in Venezuela." CTC Sentinel 12(7): 31–36.

DeLanda, Manuel. 1997. A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History. New York: Zone Books.

Easterling, Keller. 2014. Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. London: Verso.

Gilbert, Chris. 2023. Commune or Nothing! Venezuela’s Communal Movement and Its Socialist Project. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Hetland, Gabriel. 2023. Democracy on the Ground: Local Politics in Latin America's Left Turn. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lavelle, Daniel. 2013. A Twenty-first Century Socialist Agriculture? Land Reform, Food Sovereignty and Peasant–State Dynamics in Venezuela. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 21(1): 133–154.

Mitchell, Timothy. 2011. Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil. London: Verso.

Monaldi, Francisco, Igor Hernández, and José La Rosa. 2020. The Collapse of the Venezuelan Oil Industry: The Role of Above-Ground Risks Limiting FDI. Houston: Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

Platias, Anthanasios. 2026. Venezuela and the Geopolitical Consequences of American Intervention. Modern Diplomacy.

Thom, René. 1975. Structural Stability and Morphogenesis. Reading, MA: W. A. Benjamin.

Tooze, Adam. 2026. Chartbook #423: Some topical material on Venezuela. Hopefully useful. Substack.

Velasco, Alejandro. 2015. Barrio Rising: Urban Popular Politics and the Making of Modern Venezuela. Oakland: University of California Press.

Webber, Jeffery R. 2017. The Last Day of Oppression, and the First Day of the Same: The Politics and Economics of the New Latin American Left. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Weisbrot, Mark, & Jeffrey Sachs. 2019. Economic Sanctions as Collective Punishment: The Case of Venezuela. Center for Economic and Policy Research.