W. V. O. Quine and the Universal Set

1. The Library and the Censor

To practice the philosophy of mathematics today is to accept an incomplete reality. The dominant paradigm, the "Iterative Conception of Set" codified in Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory (ZF), models the mathematical universe as an ever-expanding hierarchy. It bootstraps from the void of the empty set, climbing the transfinite ordinals layer upon layer, a recursive ascent ad infinitum (Boolos 1971, 221).

Peter Aczel observes that the restriction to well-founded sets was "institutionalised" not because extraordinary sets are impossible; rather, the standard abstract objects of mathematics happened to be representable without them (Aczel 1988, xvii). Pragmatism calcified into dogma.

The schism is structural. Orthodox ZF set theory evades paradox through a "limitation of size": it declares that the "Universe" is an overgrown multiplicity, too vast to be encapsulated as a set (Forster 1995, 1). It sacrifices the Whole to save the hierarchy. Willard Van Orman Quine refused this sacrifice. His "New Foundations" (NF) operates on what effectively amounts to a limitation of syntax (Quine 1937, 70). It posits that the Universe (V) exists as a set, but restricts the comprehension schema—our capacity to define subsets—to those formulas that are "stratified." In NF, the limitation lies in the grammar of our access, preserving the ontology as One.

Randall Holmes notes that orthodox type theory creates a "hall of mirrors." Mathematical objects like the number 3 are endlessly reduplicated at every level of the hierarchy—a distinct '3' for integers, another '3' for sets of integers, ad infinitum (Holmes 2023, 10). Quine refused to accept this infinite redundancy. He collapsed the reflections into a single, actual object.

For this architecture hides a fatal flaw: it ensures the Universe is never finished. In ZF, the collection of all sets is too large to exist. It is a "Proper Class," a phantom that haunts the periphery of the formalism but is forbidden from entering it (Forster 1995, 1).

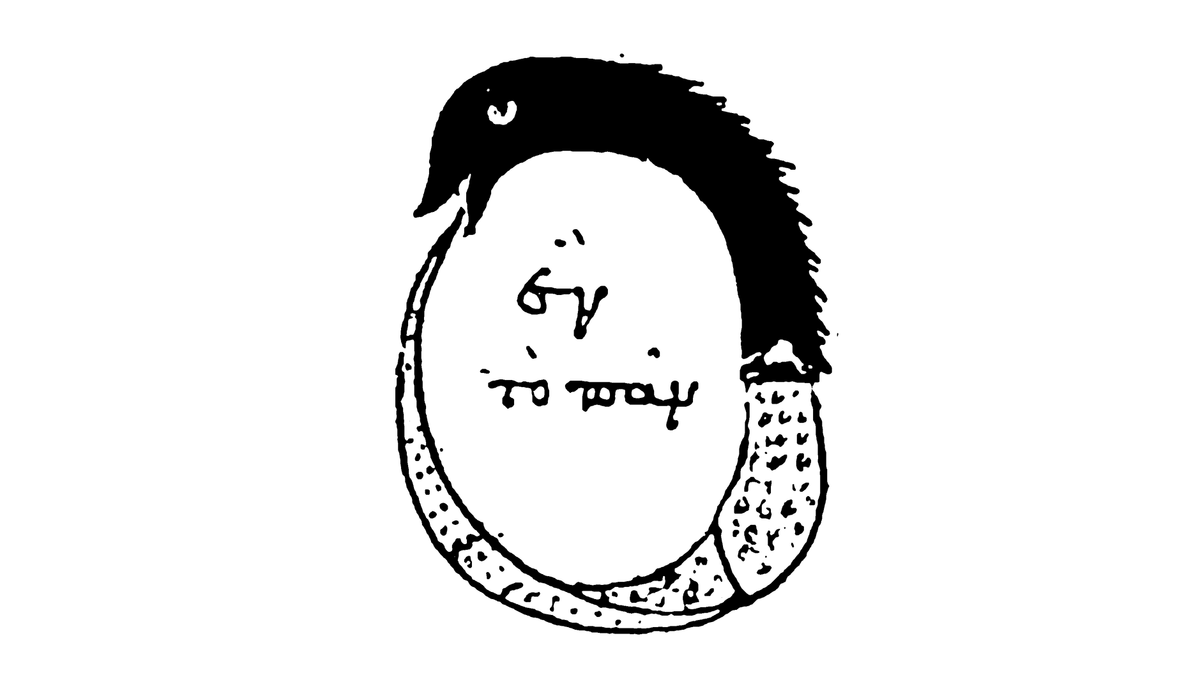

This restriction is less technical sanitation than containment protocol. ZF was built to fence off the abyss rather than map the cosmos. It is a sanctuary for mathematics, constructed because the view from the edge of the Monist Universe, the vertigo of the Paradoxes, was too overwhelming to endure. It implies that reality is fundamentally fragmented, an "Open Multiplicity" that can never be totalized. For Substance Monists, the orthodoxy of ZF is metaphysically bankrupt. These thinkers, adhering to the Spinozist conviction or the ancient dialectic of Plato’s Parmenides, interrogate the formidable unity of "The One" against the fragmented existence of "The Many." The iterative hierarchy offers a Library of Babel of infinite complexity rigorously forbidden from containing its own catalog. It fears the "cyclical book" that Borges' mystics claimed was God, denying the "sphere whose exact center is any hexagon and whose circumference is unattainable" (Borges 1962a, 113).

This censorship has consequences that modern theorists of "Absolute Generality" struggle to reconcile. Rayo and Uzquiano frame two questions: the "Metaphysical Question" (does the all-inclusive domain exist?) and the "Availability Question" (can we quantify over it?) (Rayo and Uzquiano 2006, 2). ZF answers "No" to the first, forcing a retreat into an endless potentiality of sets. A system like NF allows for a "Total Totality"—a domain that includes absolutely everything, including itself.

Introduced by Quine in a moment of insurrection against the Theory of Types, NF is the logic of the "Actual Infinite." It stares down Russell’s Paradox and asserts the necessary existence of the Universal Set (V). But this assertion is not merely a syntactic protest. As Quine detailed, the logic of this Total Universe shifts from an open-ended schema to a rigid structure built from a "far more meager" array of logical notions: membership, universal quantification, and alternative denial (Quine 1937, 71).

The "One" is no vague mystic unity; it is a closed, operational system. To navigate it, we must abandon the safe, well-founded ladder of the hierarchy for the recursive web of the Graph. As Peter Aczel visualized in his study of non-well-founded sets, the topology of such a self-containing reality is an "accessible pointed graph," a network where chains of being curve back upon themselves, allowing the Universe to behold itself. In NF, the Universe is a concrete object. It is a member of itself (V ∈ V) and is rigorously closed under the operations of a complete Boolean algebra.

The price of admission to this Monist universe is what logicians call "diabolical." In 1953, Ernst Specker proved that in a consistent NF universe, the Axiom of Choice must fail (Specker 1953, 972). The "One" exists, but it refuses to be well-ordered. It is a "Forbidden Book" less because it contains all sets than because its internal structure defies the clean, orderly sorting promised by the iterative hierarchy.

We are here to explore the "Diabolical" reality of that forbidden universe.

2. From Types to Stratification

To understand the radical nature of Quine's proposal, we must understand the trauma that birthed it. In the early 20th century, Bertrand Russell shattered naive set theory with his eponymous paradox: Consider the set of all sets that are not members of themselves (R = {x | x ∉ x}). Is R a member of itself?

If it is, it isn't. If it isn't, it is.

To arrest this logical explosion, Russell constructed the Theory of Types. He stratified the universe into a rigid hierarchy where an object of Type 0 could only belong to a set of Type 1, which belongs to Type 2, and so on. This resolved the paradox, but at a terrible aesthetic cost. It created what T.E. Forster calls a system of "reduplication," where the number 3, for instance, is instantiated infinitely—once at Type 0, again at Type 1, again at Type 2 (Forster 1995, 22). This echoes the heresy of Uqbar recorded by Borges: "Mirrors and fatherhood are abominable because they multiply and disseminate that universe" (Borges 1962b, 4). Quine stepped through the glass, collapsing the infinite corridor of reflections into a single, self-regarding substance.

In 1937, Quine published "New Foundations for Mathematical Logic," creating a system that flattened Russell's hierarchy back into a single plane of existence. His innovation was to decouple the types from the objects and re-embed them in the grammar.

2.1. Transcendental Syntax

This creates a condition of "systematic ambiguity." In the pre-Quinean view described by Tarski, truth was stratified; a statement could be true at one type level but meaningless at another (Holmes 2023, 6–7). Quine enforced this ambiguity as a permanent feature of reality.

- In ZF, we avoid paradox by a Limitation of Size: objects that are "too big" (like the Universe) are banished from existence.

- In NF, we avoid paradox by a Limitation of Expression: the Universe is infinite, but our capacity to describe subsets is constrained by a "Transcendental Syntax" known as Stratification.

If standard set theory is a Skyscraper, built one floor at a time, strictly ordered, with no top floor, New Foundations is a Hall of Mirrors. But unlike the redundant hall of Type Theory, where every reflection was mistaken for a separate object, this hall reveals the same object from infinite angles. In this recursive architecture, everything reflects everything else according to strict symmetries. You can see the whole within the parts, but only if you follow the rigid laws of reflection.

The Orthodoxy defends the Skyscraper by claiming sets are "formed" in stages, relying on the metaphor of the "lasso"—one cannot ensnare the lasso while casting it (Boolos 1971). But this confuses ontology (what exists) with epistemology (the process of us finding it). It mistakes map-making for the territory. In Monism, the sets are not built by our lasso in time; they are defined by eternal logic. The house is pre-fabricated; ZF is just a manual for building it brick by brick.

In NF, strict operational logic dictates that a formula defines a set if and only if it satisfies the condition of stratification. Think of this not as building a skyscraper with distinct floors (Type Theory), but as speaking a language with a rigid grammar. The objects themselves are not sorted; they all inhabit the same flat ontological plane. Our access to them, however, is filtered through a linguistic lens. We can only "see" or define those collections that our grammar allows us to articulate without incoherence. This syntactic filter requires that we can assign integer indices to variables such that for every occurrence of membership (x ∈ y), the type of y is exactly one higher than the type of x (Quine 1937, 76). The grammar enforces the hierarchy so the world doesn't have to:

- The Universal Set (

V) exists because the formulax=xis stratified (we can assignxto type 0). - The Russell Set (

R = {x | x ∉ x}) is strictly forbidden, because the formulax ∉ xrequiresxto be one type higher than itself, a logical impossibility.

This represents a structural containment of the paradoxes rather than a denial of them. By enforcing stratification, NF creates a "One World" ontology where the hierarchy is an illusion of language rather than a feature of reality. It is a system where, as Quine put it, "all mathematics is translatable into logic"—but a logic stripped down to its barest, most ruthless essentials (Quine 1937, 70).

3. Substance Monism

Why choose this path? Why not accept the "multiverse" of ZF? New Foundations allows for a rigorous Substance Monism, satisfying the metaphysical demand that "Everything" must be a valid concept.

In the ZF orthodoxy, the universe is an "unfinished" process. If you try to group "everything" together, the logic forces you to create a new, larger container outside the group. This leads to the modern debate on Absolute Generality: the suspicion that we can never truly quantify over "absolutely everything" because the domain of quantification keeps expanding (Rayo and Uzquiano 2006, 2).

Von Neumann solved this paradox of size by inventing "Proper Classes"—collections that are too big to be things. This is the logic of the Potemkin Village. To keep the mathematics "rich" and "generous," allowing for powerful theorems like the Axiom of Choice, ZFC erects the facade of ghost objects that have members but cannot be members. They allow the machinery of mathematics to operate, but they have no ontological depth. Monism restricts the architecture (Stratification) to ensure that every object is real.

NF cuts this Gordian knot. It asserts that the Universe (V) is the extension of the predicate of self-identity (x=x). If the Universal Set exists, then Holism is mathematically true, and the Atomism of ZFC is revealed as a useful fiction. As Forster argues, "if one thing is certain in this life, it is that everything is identical with itself" (Forster 1995, 1). Therefore, the extension of this predicate—the Universe—must exist. There is no "outside." The universe is a Complete Boolean Algebra.

- Closure: If you take any set A, the "complement" of that set (everything in the universe that is not A) is also a valid, existing set.

- Self-Reflexivity: The universe contains itself (

V ∈ V). It acts as the Spinozist Substance—the Causa Sui (cause of itself) that explains its own existence (Spinoza 1677, I, Def 1).

This closure allows for a startling logical compression: unlike ZF, which requires an infinite schema of axioms to handle its hierarchy, the Monist universe of NF can be finitely axiomatized (Hailperin 1944, 2). Rather than an endless list of regulations, the laws of the "One" form a finite, compact seed from which the total complexity of the universe unfurls.

This requires us to view logic as a tool for definition (carving sets out of the pre-existing block of the Whole) instead of construction (building sets from blocks). It is a static, closed, and singular diamond. The "rudimentary language" of the system—variables, membership, and denial—forms a cage from which nothing can escape; there is nowhere else to go.

This shift forces us toward Ontic Structural Realism. In a Monist universe without the Axiom of Choice, individual "things" lose their distinct identity. As we will see, objects can become "indiscernible," melting into a background of perfect symmetry. In this view, the Substance of reality is not the sets themselves, which can be messy and ill-behaved, but the rigid stratification structure that binds them.

4. A Continent Mapped, A Modern Vindication

For nearly a century, this system lay under the shadow of inconsistency. Unlike the safe iterative hierarchy, the circular loops of NF were suspected of hiding contradictions. It was the Wild West of logic: a place where the Axiom of Choice failed, where counting didn't work as expected, and where the standard rules of behavior broke down.

It is a testament to the radical nature of this Monism that even Quine eventually turned his back on it. After Specker proved the failure of Choice in 1953, Quine the Pragmatist overruled Quine the Logician. He chose the safe utility of ZFC over the diabolical truth of his own creation. We are picking up the weapon that Quine dropped.

For decades, the only way to keep the Monist dream alive was to compromise it. In 1969, Ronald Jensen proved the consistency of NFU (New Foundations with Urelements), a safe version of the theory that allowed for atoms, or non-set objects. This fractured the Monist project. NFU became a working theory that preserved the Universal Set without the diabolical failures of standard logic. But Pure NF—Quine’s original, uncompromising vision of a universe made of nothing but sets—remained a hard logical puzzle, a treacherous system whose consistency was an open wound in logic.

That changed in 2025. With the recent verification of the consistency of New Foundations by Randall Holmes and Sky Wilshaw, utilizing the proof assistant Lean, the status of this reality shifted from speculation to geography. We are no longer discussing a hypothetical realm; we are standing on the shore of a newly mapped continent (Holmes and Wilshaw 2025). For ninety years, the mathematical establishment treated this land as a mirage—a likely inconsistency. Now we have the map. The Monist Universe exists. But as the map reveals, the terrain is hostile. It is a beachhead, not a cathedral.

This vindication reignites the debates on formalization and ontology. If a "Theory of Everything" is consistent, then the ZF prohibition on the Universal Set is not a logical necessity; it is a choice. We have chosen to fragment the universe to make the math easier. Furthermore, this opens new doors for Category Theory. While ZF struggles to handle "Large Categories" (like the Category of All Sets), treating them as proper classes outside the theory, NF welcomes them as citizens. It offers a potential foundation where the structures we use to describe reality are part of reality itself.

In the ZF orthodoxy, entities like the "Category of All Groups" (Grp) are treated as mere façons de parler—figures of speech that must be eliminated from precise formal statements (McLarty 2008, 2). To speak of them, one must invoke "Grothendieck universes," which are merely large sets pretending to be universes (McLarty 37). NF, by contrast, offers the possibility that the Category of Categories is not a fiction, but a legitimate citizen of the ontology.

5. The Diabolical Compromise

We have established that the Book of Everything exists. We have established that its Universe is One. But this Totality comes with a steep price.

Randall Holmes uses the term "Diabolical" to describe the models of NF. This refers to the severe ontological price we pay for admitting the Universal Set. To allow the Universal Set to exist without exploding into paradox, we must twist the internal logic of the universe. The symmetries of this Monist world are so perfect, so pervasive, that they destroy our ability to distinguish the parts from the whole.

The primary casualty is not just the Axiom of Choice (AC), but counting itself. In the standard ZFC universe, we assume we can reach into an infinite number of bins and select one object from each. It is a materialist universe of discrete "things." In the monistic universe of NF, this intuition fails catastrophically. As noted, Ernst Specker’s 1953 proof demonstrates that NF disproves the Axiom of Choice (Specker 1953, 972).

This result is double-edged. Specker’s proof does not merely destroy Choice; it enforces Infinity (Holmes 2023, 11). In the Monist universe, the Whole cannot be finite. If the universe were finite, it could be well-ordered. Therefore, its very refusal to be ordered proves its endless magnitude. Furthermore, Forster and Holmes highlight that standard NF may fail to satisfy the "Axiom of Counting" (AxCount≤), meaning the universe cannot even map the standard integers to its own singletons (Forster 1995, 30).

We find a metaphysical precedent for this failure in Borges' Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius. In the idealist world of Tlön, positing distinct, persistent objects is considered the "heresy of materialism." Borges recounts the "sophism of the nine copper coins," in which heretics attempt to prove that coins lost on Tuesday are identical to those found on Friday. The orthodox defenders of Tlön dismantle this claim, arguing that "equality is one thing and identity another" (Borges 1962b, 11).

In NF, we face the same vertigo. The symmetries of the Universal Set are so perfect that individual elements become indiscernible. We cannot "pick" the coins because the logic lacks the resolution to distinguish them. The universe cannot be well-ordered; it is an amorphous topological jelly where the operational logic of sequence breaks down at the limit (Holmes 2023, 18).

This failure is not a defect; it is the signature of a Holographic Bound. In ZF, Cantor's Theorem guarantees that the Power Set is always strictly larger than the set (|A| < |P(A)|). In NF, this theorem fails for the Universe itself. Since V contains everything, it must contain its own power set (P(V) ⊆ V). Therefore, the parts cannot outgrow the whole. The interior complexity of the Monist universe is crushed by its boundary conditions. This results in a diabolical reality where the standard axioms of counting dissolve (Forster 1995, 31).

6. The Geometry of the Prison

We have found the Book of Everything. But when we open it, we find that the pages are glued together. We cannot count the pages. We cannot "choose" a page. The price of admission to the Monist universe is the loss of linear progression. In the next post, we will explore why living in this Book means abandoning the Big Bang for a static, closed loop of infinite recurrence. We will return to the library to find that Borges was right all along: "The Library is unlimited but periodic. If an eternal traveler should journey in any direction, he would find after untold centuries that the same volumes are repeated in the same disorder—which, repeated, becomes order: the Order" (Borges 1962a, 118).

Now that we have stated the Monist universe exists, the question remains: is it knowable? Is the logical structure of this Total Universe "tight" enough to decide every basic truth, or does the admission of Everything create a reality that is fundamentally undecidable?

References

Aczel, Peter. 1988. Non-Well-Founded Sets. CSLI Lecture Notes 14. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Boolos, George. 1971. "The Iterative Conception of Set." The Journal of Philosophy 68, no. 8: 215–231.

Borges, Jorge Luis. 1962a. "The Library of Babel." In Labyrinths: Selected Stories & Other Writings. Translated by James E. Irby. New York: New Directions.

Borges, Jorge Luis. 1962b. "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius." In Labyrinths: Selected Stories & Other Writings. Translated by James E. Irby. New York: New Directions.

Forster, T. E. 1995. Set Theory with a Universal Set: Exploring an Untyped Universe. 2nd ed. Oxford Logic Guides 31. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Forster, T. E., and M. Randall Holmes. 2025. "Possible Thesis Topics in NF."

https://thomasedwardforster.github.io/thesistopics.pdf

Hailperin, Theodore. 1944. "A Set of Axioms for Logic." The Journal of Symbolic Logic 9, no. 1: 1–19.

Holmes, Randall. 2023. Introduction to New Foundations, with attention to errors of Quine. Edmonton Logic Group.

Holmes, M. Randall, and Sky Wilshaw. 2025. "New Foundations is Consistent." Preprint.

Jensen, Ronald B. 1969. "On the Consistency of a Slight(?) Modification of Quine's New Foundations." Synthese 19, no. 1/2: 250–263.

McLarty, Colin. 2008. Introduction to Categorical Foundations for Mathematics. Case Western Reserve University.

Plato. Parmenides. In The Dialogues of Plato, translated by Benjamin Jowett.

Quine, W. V. 1937. "New Foundations for Mathematical Logic." The American Mathematical Monthly 44, no. 2: 70–80.

Rayo, Agustín, and Gabriel Uzquiano, eds. 2006. Absolute Generality. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Specker, Ernst. 1953. "The Axiom of Choice in Quine's New Foundations for Mathematical Logic." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 39, no. 9: 972–975.

Spinoza, Benedict de. (1677) 1994. The Ethics. Translated by Edwin Curley. Princeton: Princeton University Press.