The Night in Which All Cows Are Black

The Cartesian Grid

Before we reach the blood, we must map the geometry of the mud. To understand the catastrophe that shattered Baruch Spinoza’s faith in human reason, we must look past the "Dutch Miracle" as a Golden Age of art and view it instead as a precarious engineering project, a fever dream of straight lines imposed on a curved earth. The 17th-century Dutch Republic was the supreme example of what Deleuze calls physical stratification, a machine made of water and will that violently captured chaotic flows into stable, profitable forms.

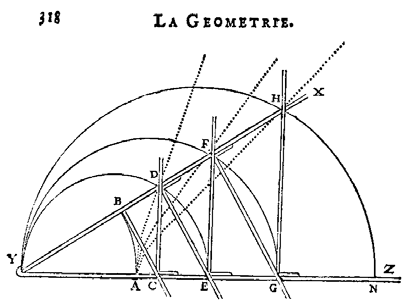

René Descartes, the architect of modern rationalism, chose to live in this damp, gray corner of Europe to develop the Cartesian coordinate system. He sat by the stove in a land manufactured from the sea, a flat plane where the Dutch had applied a grid to the earth itself. They built dykes to trap the chaotic water, forcing it into straight canals, forging solid ground from the void. This imposed a Euclidean metric ($ds^2$) onto the swamp, a triumph of the line over the curve. The ground beneath their feet testified to a single, arrogant truth: if you calculate the resultant vectors correctly, you can hold back the abyss.

At the center of this engineered miracle sat Johan De Witt, the Grand Pensionary of Holland. The tragedy that consumed him becomes clear when we realize that De Witt was not a politician in the modern, fluid sense; he was a mathematician. In his youth, he composed a treatise on the geometry of curved lines, a work of "extraordinary understanding and capacity" that allowed him to view the world as a series of vectors and forces to be balanced. He rejected the view of the world as a theatre of passions (Rowen 1978, 133). For almost twenty years, De Witt managed the Republic as if it were a complex equation. Herbert Rowen describes him as an "unphilosophical Cartesian" in politics (1978, 401). He applied a deductive mindset to governance, convinced that if legal axioms like the Perpetual Edict were correct, the state would hold. He believed with the icy confidence of a rationalist that if he engineered the geometry of the state perfectly, balancing the true freedom of the regents against the centralization of the federal union, the irrational forces of religious superstition and monarchical instinct would vanish, eliminated like a remainder term in a balanced equation.

This structural reliance mirrors the philosophical tension in the debates over Cartesian method. As Stanley Tweyman elucidates in his analysis of the Meditations, a fundamental distinction exists between Analysis and Synthesis. Synthesis is the geometer's method, demonstrating a known truth and forcing assent through "a long series of definitions, postulates, axioms, theorems and problems" (1993, 102). Analysis is the method of discovery, the "true method" which shows how the thing was invented. Crucially, Analysis requires the mind to "withdraw itself from the senses" and purge itself of prejudice (1993, 101). It functions by forcing the mind to perceive a "repugnancy"—a logical nausea—between two incompatible thoughts, compelling the intellect to abandon its bias for the necessary truth. Deleuze critiques this Cartesian haste, arguing that Descartes constructed his philosophy "too fast," stopping everywhere "at what is relative" (1968a, 323). The Dutch Grid was exactly this: a relative structure imposed on an absolute swamp.

De Witt was the state's supreme Analyst. He sought to unprejudice the Dutch mind, stripping away the sensory, emotional addiction to the House of Orange—that feudal desire for a father-king—and replacing it with the clear, distinct idea of the Republic. He believed that if he explained the geometry clearly enough, the people would see the truth. He believed the state could be cured of its passions through pure logic.

His primary instrument was the Act of Exclusion, a political axiom designed to bar the House of Orange from seizing the Stadtholdership. He viewed the young Prince of Orange as a variable introducing unacceptable instability, rejecting the mob's messianic reverence. In his famous "Deduction," De Witt argued that the state's "old form and order" required the sovereignty of the provincial assemblies, untainted by the "eminent head" of a Prince (Rowen 1978, 239). It was a proof, elegant and bloodless. He wrote to his ambassadors with the precision of a geometer, demanding they report the "countenance and expression" of foreign kings, treating diplomacy as data collection for his great calculation (Rowen 1978, 385).

Yet, a fatal error lurked in this calculation, one that resonates in our own era. De Witt was trapped in what Étienne Balibar calls "constitutional illusions," the belief that rights existing on paper (the Cartesian grid of the law) could contain the "physical, actual sense" of power (1990, x). He assumed the Multitude was a set of rational points on his grid, capable of alignment by the Natural Light of reason. He failed to account for the fear of the masses, believing that a rational, legalistic framework could contain the irrational forces of the mob (1990, 16). He failed to see what Antonio Negri calls the 'Savage Anomaly'. De Witt represented Potestas—the constituted command of the State. The mob represented a warped Potentia—the constituent power of the multitude. The tragedy of 1672 was the collision of these two forces (2000, 191). Negri, in his optimistic reading of Spinoza, argues that the "multitude" is the positive, constituent power (potentia) of society, a collective force that "transforms what was a Renaissance, utopian, and ambiguous potentiality into a project... of collectivity" (2000, 21). For Negri, this constituent power is the hero of history, the vibrant force of the many that creates democracy.

The Grand Pensionary's fate suggests a darker reality, one Spinoza was forced to witness. The constituent power Negri celebrates did not manifest as a liberating collective imagination. It manifested as a hungry, shapeless beast. The multitude was not interested in the Republic's constituent project. They were what Marx described as an incoherent mass, unable to organize the curve of their own lives. "They cannot represent themselves, they must be represented," Marx observed. "Their representative must at the same time appear as their master" (1852, 110). They wanted the warm, superstitious comfort of a King. Negri claims that "in Spinoza Power yields to freedom" and that the anomaly is the "radical expression of a historic transgression" (2000, 20–21). But in the streets of The Hague, the transgression was not liberation; it was regression. The multitude did not want De Witt’s true freedom, which demanded the hard work of rationality; they wanted the corrupt imagination and superstition that Spinoza identified as the monarchy's tools.

The grid was fragile. While De Witt and the regents sat in the Statenzaal, adding neoclassical wings to medieval buildings and refining their deductions (Rowen 1978, 334), the swamp rose beneath them. Physical stratification failed. The dykes of reason held back a sea of inadequate ideas—passions, fear, the frantic desire for a savior. Spinoza, grinding his lenses in the quiet suburbs, understood this geometry better than De Witt. He knew the Geometric Method of his Ethics was not just a way of writing; it was a fortress built against chaos (1677b, 1). But even Spinoza could not calculate the velocity of the stone that would shatter the glass.

The Cartesian Grid was a beautiful lie. It presumed the state was a flat plane of commerce and tolerance where every citizen had a rational address (x,y). But the third dimension—the depth of the mud, the height of the mob’s fury—was invisible to the Grand Pensionary. He looked at the map and saw a Republic; the people looked at the territory and saw a void where a King should be.

As we watch the events of our own time, where immigration police—forces long known for their repression of moral, hard-working immigrant families—now turn their weapons on 'ordinary citizens,' we see the final collapse of the Cartesian distinction. The grid no longer separates the citizen from the Other; the machinery built to exclude the outsider has turned inward, devouring the very population it was sworn to protect. The logic of the state is always Euclidean; the logic of the street is always fractal, bloody, and hungry.

For a moment, the Grid held back the Sea. But the water grew colder, and the crowd gathered at the prison gate, hungry for the meat of the mathematicians.

Projective Collapse

The Dutch Republic's geometry was an engineering miracle, but Euclidean grids are brittle; they rely on a fixed vanishing point, a center that must hold. In 1672, that center gave way. The Rampjaar (Disaster Year) was an ontological collapse, far more than a military defeat. When Louis XIV's French army breached the border, the Grid did not just bend, it dissolved. Defenders opened the dykes in a desperate, suicidal attempt to stop the invasion, turning orderly farmland back into primeval swamp. It was a ritual un-creating of the country. In this mud, amidst the rising waters of panic, the Orangist faction—Monarchists and Calvinists who chafed under the Republican oligarchy's bloodless geometric hubris—seized their moment. They unleashed the Body without Organs in its most volatile form, the Mob.

On August 20, 1672, The Hague did not resemble a political protest; it resembled a failing pressure vessel. The city, usually "so lively, so neat, and so trim that one might believe every day to be Sunday," was "swelling in all its arteries with a black and red stream of hurried, panting, and restless citizens" (Dumas 1850, 3). This was no longer a collection of individuals with distinct Cartesian coordinates. It was a topological singularity—a point where the smooth manifold of the state ceased to be differentiable, collapsed by the imitation of affects. Spinoza defines this mechanism as a feedback loop where imagining another’s emotion causes us to feel the same emotion, creating a contagion of rage that geometric logic cannot contain (Kisner 2018, 57). The mob dragged Johan and Cornelis De Witt, the engineers of True Freedom, out of the Gevangenpoort and onto the Buytenhof—the stone threshold separating the sanctum of the State from the city. What followed was a projective collapse. In the Republic's civilized space, law, dialogue, and architecture maintain a mediated distance. But on the Buytenhof, that distance collapsed to zero. The crowd's screaming intensity obliterated the space required for the Other to exist.

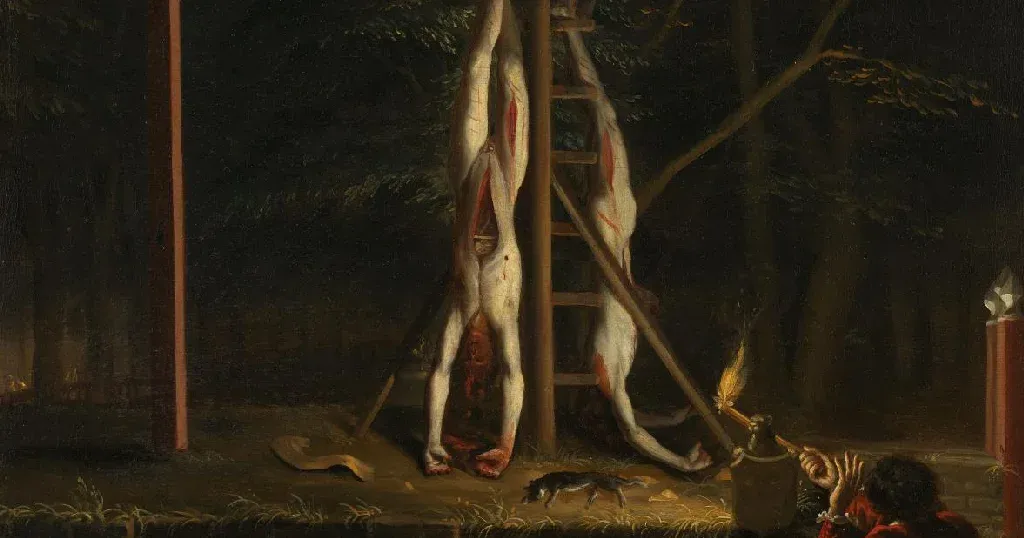

The rioters did not just kill the brothers; they sought to unmake them. They stripped them, butchered them, and in a paroxysm of "cannibalistic hysteria," consumed them (DeSanto 2018, 93). The corpse of De Witt became what Deleuze calls a simulacrum: "not just a copy, but that which overturns all copies by also overturning the models" (1968b, xx). In devouring the Prime Minister, the mob devoured the model of the State itself.

This brutality was a ritualistic punishment, distinct from a chaotic riot. The mob, facilitated by the schutterij (civic militia), usurped the judiciary's role to punish traitors the state had failed to condemn (DeSanto 2018, 1–4). Hegel, describing the absolute indiscernibility of a substance without distinction, famously spoke of "the night in which all cows are black." He argued that Spinoza’s monism swallows all finite things into an undifferentiated abyss (Melamed 2013, 63). While intended as a philosophical critique, the phrase captures the lynch mob's metaphysical erasure. In the Rampjaar frenzy, all political nuance, history, and humanity were erased in a monochrome wash of violence. Spinoza, however, would insist that this erasure is a misunderstanding. Finite modes are not illusions; they are propria—properties following from God's essence (Melamed 2013, 78). To deny the reality of the modes is to deny the productivity of God’s power. In the street, this proper order was inverted. The night was not the calm of substance, but the void of the mob's pure immediacy. Being and Nothing, as Hegel argued in his Science of Logic, vanish into one another; in the mob's pure immediacy, "the one is not distinguished from the other," and the resulting state is a void (1812, 60).

Moreover, the attack was intimate, "body-to-body," a reclamation of power through the visceral destruction of the state's representatives (DeSanto 2018, 92). It was not enough to kill; the bodies had to be unmade. Dumas describes the crowd not just as a stream, but as citizens with "knives in their girdles," dismantling the body politic by dismantling the bodies of its leaders (1850, 3). The crowd "slashed the two bodies open lengthwise, cut out the hearts and tongues... and slit off the ears, fingers, toes, and noses" (DeSanto 2018, 93). This was the finger of the state severed by the populace's teeth. Spinoza, the lens grinder who sought to view the world sub specie aeternitatis (under the aspect of eternity), was forced to look upon this: the Humanist reliance on reasonable people acting reasonably had shattered under the vulgus—the masses he feared. His reaction was visceral. He attempted to run into the street to post a placard reading Ultimi Barbarorum ("The Ultimate of Barbarians") at the site of the massacre, only to be physically restrained by his landlord, who locked the door to save his life (Kisner 2018, xli). In that locked room, he realized the Cartesian Grid was insufficient. It was too rigid. It had ignored the passions of the body social (Balibar 1990, 45).

The King and the Revolutionary

Here lies the strange, melancholic irony of 17th-century politics—a paradox echoing our own present, where state power and mob violence blur into a single vector.

The Orangists believed they fought for freedom against Louis XIV, the Sun King and arch-symbol of Absolutism. They rallied around the Prince of Orange, believing him the champion of their local privileges. Yet, metaphysically, the Orangist mob represented a purely chaotic force—an anti-structure demanding the right to be irrational, governed by tribal passion instead of state reason.

Conversely, Spinoza and De Witt—the Republicans—shared a secret, structural DNA with their enemy, Louis XIV. As Alexis de Tocqueville observed, revolutions claiming to overthrow monarchies often perfect the monarchy's deepest project: centralization. The Revolution of 1789, like De Witt's Republican project, "centralized the whole governmental machinery once again," creating a power "stronger and much more autocratic than the one the Revolution had overturned" (1856, 280).

- Louis XIV said, "L'État, c'est moi" (I am the State)—a terrifying assertion of central order.

- Spinoza’s God says, "Substance is One"—an equally absolute assertion of central order.

Both the absolutist King and the rationalist Republican engaged in the Geometric Spirit—imposing a Universal Grammar to crush the local, feudal, and superstitious. They sought to streamline the state into a machine. Karl Marx noted how state power, with its "enormous bureaucratic and military organization," functions as an "appalling parasitic body" enmeshing the social body (1852, 108). This state machinery does not disappear with a regime's fall; it is transferred, perfected, and expanded.

The De Witts managed this machinery in its Dutch Republican form. They were the Grid's agents. The Orangist mob represented the multitude—the chaotic, seething ocean refusing to be gridded. The mob that ate the De Witts attacked the abstraction of the State itself, driven by a fear of the masses Spinoza identified as the fundamental instability of all political orders (Balibar 1990, x). Spinoza saw that the mob had the right to kill De Witt only because they had the power to do so—a terrifying realization of his own axiom that right is co-extensive with power (tantum juris quantum potentiae) (Negri 2000, 183). He saw that if Reason were to survive the Ocean of the multitude, it could not simply build a higher dyke. The "peace and security of life" could not be guaranteed by high ideals alone (Spinoza, quoted in Balibar 1990, 51). Reason had to go underground. It had to become a submarine.

Consider the Lobster

The smell of roasted meat—human meat—lingers in The Hague. It clings to damp wool coats and settles in the brickwork of the Groene Zoodje, an olfactory ghost that refuses to be exorcised by the sea breeze. When Spinoza returned to his room on the Paviljoensgracht, bypassing the crowd that had torn the De Witt brothers into wet ribbons, he returned a man watching a physics experiment fail, no longer the saint of Rationalism. The Dutch Republic's Euclidean grid, that Cartesian dream of flat, manageable space, had not just broken; the mob had chewed it up. The Mob did not respect the grid. The Mob moved in swirls, eddies of inadequate ideas gathering force until they became a tidal wave of hate.

He realized that the geometry of the line was insufficient. If you build a wall of simple reason, the mob will climb it, because the mob is fluid and the wall is static. To survive the Rampjaar—and history's inevitable repetitions, right up to the spectacle of border agents executing citizens on American asphalt—he needed a geometry that could explain why the loyal soldier becomes a butcher. He needed a trap. He needed a topological machine.

Negri argues that the Dutch "Golden Age" was a capitalist project masking social contradictions with a Cartesian ideology of peace (2000, 8). Spinoza’s metaphysics exposes the savage reality beneath this bourgeois peace. He sat down to finish the Ethics as a system of stratification. It was no manifesto of joy. Deleuze describes the Double Pincer or the Lobster as a mechanism where liquid flows are captured and locked into rigid strata. Spinoza, staring at the ceiling while the screams died down outside, began to construct exactly this: a fibration.

In topology, a fibration is a structure $\pi: E \to B$ that maps a complex Total Space ($E$) onto a simpler Base Space ($B$) while preserving the local structure of the fibers. It is not just math; it is a spell for binding chaos.

1. The Base Space ($B$): The raw meat of the world—the molecular flows, the chaotic biological and affective surges of the multitude. It is the mob in the street, the adrenaline in the veins of the police officer, the sheer, blind conatus of survival.

2. The Total Space ($E$): The structure built on top of it—the molar form, the State, the Law, or in Spinoza’s case, the Ethics itself. The diamond cage.

3. The Projection Map ($\pi$): The function that locks the fiber over the base, ensuring that every point in the Total Space maps rigorously to a point in the Base.

Spinoza’s turn to Necessity was a tactical deployment. Far from seeking refuge in abstract logic, he constructed an ontological weapon. Geometry is a system where consequences follow from definitions without choice; a triangle does not "decide" to have 180 degrees. By writing the Ethics as a geometry textbook, Spinoza asserted that reality is a logical system, not a Kingdom. No King, human or Divine, decides. There is only the automaton of logical consequence. The Rampjaar shattered the optimistic, contractual framework of his earlier Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (TTP). In the aftermath, he abandoned the social contract entirely in favor of a physics of power, a shift fully realized in the Tractatus Politicus (TP) (Balibar 1990, 50). If contingency exists—if things could be otherwise—then the mob is right to hope, and therefore right to kill for that hope. If the State could be different, then the armed agent is justified in his terror. But if everything is Necessary, if the flow of reality is a rigid, unyielding fiber that cannot be bent, then the energy of the mob dissipates against the stone of the Infinite.

Here the Ethics' melancholic nature reveals itself. It is a book written by a man engaging in a desperate act of stratification. As Deleuze observes in Difference and Repetition, this involves a differentiation where the virtual is actualized into a concrete, inescapable system. Spinoza builds a God that does not judge, does not love, and most importantly, cannot change. This God is the Base Space.

Structurally, the work is a topological trick. He invites you into a Double Pincer. The first pincer destroys your illusions: free will, good and evil, teleology. He strips you bare, reducing you to a mode of substance, a degree of power (Deleuze 1968a, 92). The second pincer reconstructs your mind into a mirror of Divine Necessity. He locks you into the fiber. The mob stays outside. They cannot climb this wall because there are no footholds of hope or fear. There is only the smooth, vertical surface of Eq. 1, the definition of God.

Its true genius lies in its cruelty. It strips human beings of free will, revealing them as spiritual automata. This term, haunting the Ethics, unlocks both the cannibalism of 1672 and 21st-century police violence. In Expressionism in Philosophy, Deleuze notes that for Spinoza, "we are produced by external things, we are 'spiritual automata'" (1968a, 140). We do not author our thoughts; we process them. The mob that ate the De Witts was not evil in the Christian sense; it was a mechanism reacting to inputs—fear, propaganda, the sad passions manipulated by the Orangist clergy.

This reflects on the present. When we witness the specialized violence of deportation squads—modern-day Janizaries of capital—redirected toward the general populace, we witness the same mechanism. We ask: "How could they do this? Where is their humanity?" Spinoza answers: They have none, in the way you define it. They are automata. But they are functioning exactly as designed, not broken robots. They are operating under a compulsion that feels like freedom.

Frédéric Lordon, in Willing Slaves of Capital, uses Spinoza to dissect this illusion of consent. He argues that power's ultimate achievement is aligning the desire of the subject with the 'master-desire' of the institution. The police officer, the soldier, the Orangist rioter—they are not acting against their will. They have been enlisted. Lordon writes, "The employment relation is thus a relation of enlisting [enrôlement], the essence of which is to make other powers of acting join in the pursuit of one's own industrial desire" (2014, 11). This is vector colinearization: a machine for manufacturing compliance that discards force in favor of geometry. The master-desire aligns the individual vectors of conatus such that their sum points strictly in the direction of the State's design.

In the Fibration, the State's master-desire acts as the Projection. It captures the raw conatus of the individual (Base Space) and maps it onto the rigid structures of the Institution (Total Space). The individual feels he acts freely—he feels righteous anger as he pulls the trigger or wields the knife—but he merely travels along a fiber laid down before he was born. He is a willing slave because his capacity to feel joy has been hijacked. "The master-desire captures the power of acting of the enlistees," Lordon explains. "It makes the conative energies of others work in its service" (2014, 30).

The philosopher witnessed this in his friends' butchered bodies. He realized you cannot argue with a spiritual automaton using Reason or Morality, because the automaton does not operate on those frequencies. It operates on Affect. The only way to stop the machine is to build a bigger, stronger machine.

Thus, the Ethics becomes the Lobster shell. It is a rigid structure, a term Melamed emphasizes in his analysis of Spinoza’s metaphysics. Melamed argues for a strict bifurcation in Spinoza’s system, a structural cleavage that disallows human caprice from altering God's nature (2013, 262). The Ethics' fibration is Spinoza’s mental fortress. By accepting the Base Space—the Definitions, the Axioms, the absolute Necessity of all things—the reader is projected into a Total Space where the passions of the mob cannot reach.

If you understand that the policeman killing the unarmed man is an automaton driven by a master-desire that is essentially an algorithm of state preservation, you cease to be angry in a way that destroys you. You enter a state of cold, clinical understanding. You see the connection of causes. You see the fibration. But this safety comes at a price. It requires the liquidation of the human subject as we romantically conceive it. There is no "I" outside the machine. As Deleuze puts it, "The power of thinking is what constitutes the form of an idea as such" (1968a, 136). We are thoughts in the mind of God, or gears in the machine of Nature.

As we look at the news feeds, at the grainy footage of state violence, at our own Rampjaar, we should not look for justice in the Euclidean sense of balancing scales. We are watching rigid bodies collide, tectonic plates grind. The armed agent is a mode of extension acting under a master-desire of control. The victim is a mode of extension acting under the conatus of survival. The collision is Necessary.

In the quiet aftermath, Spinoza polished his lenses, grinding the glass until it was perfectly smooth. He tried to see the wires of the automata. He tried to see the trap's fibers. He found that the only way to be free of the Lobster was to become the Lobster—to become so hard, so geometric, so aligned with the crushing weight of Necessity, that the world's teeth could no longer find purchase on his skin. It was the only way to ensure that when the next mob came, they would break their teeth on his joy.

Univocity and the Internal Language

The screaming stops. The Hague scrubs the De Witt brothers' blood from the cobblestones. The water runs thick in the gutters, carrying away the debris of a Republic that failed to protect its architects from the mob's cannibalistic rage. But inside his rented room on the Paviljoensgracht, Baruch Spinoza is building a bunker, a citadel of adequate ideas. He constructs a geometry so dense, so hermetically sealed, that no mob, no Stadtholder, and no sudden knock at the door can penetrate it.

He begins by rejecting the very thing that got Jan and Cornelis De Witt killed: the illusion of the Subject. The brothers died because they were men, distinct individuals, subjects standing apart from the mob, trusting in a social contract that dissolved the moment the knives came out. Spinoza realizes that to survive, one must cease to be a subject. He retreats from the streets' unpredictable contingency into the Ethics' absolute necessity. Spinoza shifts from the discrete vulnerability of Set Theory ($x \in S$) to the relational impregnability of a Topos, a fortress where truth is structural.

This is a retreat into the floorboards, into the light caught in the lens, into the dust motes dancing in the air. It is a microscopic exile. It avoids the clouds. Deleuze identifies this shift as the move toward Univocity. In the old world—the world of Monarchs and transcendent Gods—Being was equivocal. God "was" in a way fundamentally different from how a man "was." God was the General; man was the foot soldier. This hierarchy is fatal because it allows for judgment, for the exception, for the King to point a finger and declare a life forfeit. But Spinoza levels the hierarchy. He declares that God is the cause of all things "in the same sense" that he is the cause of himself (Deleuze 1968a, 163). "The relation of expression," Deleuze writes, "does not ground between God and world an identity of essence, but an equality of being" (Deleuze 1968a, 175). This is the bunker's Flat Ontology. There is no Z-axis where a King or a God sits in judgment. There is only the X-Y plane of pure, immanent existence. By asserting that "attributes are formally affirmed of substance" and that this affirmation is "univocal" (Deleuze 1968a, 59), Spinoza ensures that there is no outside for the mob to come from. The violence is no longer an invasion; it is merely a bad configuration of data within the system.

A bunker requires a code, a cipher, a language independent of the treacherous words of politicians or priests. Spinoza finds this in the Internal Language of a Topos. In Sets—the mob's logic—truth is external; you point to a thing and say "that is a traitor," and if the external power agrees, the correspondence kills him. In a Topos, truth is not binary; it is defined by a subobject classifier ($\Omega$), a complex object of internal structural coherence (Goldblatt 1984, 84). The logic is local. As Goldblatt notes, in a Topos, "the logical principles that hold... are those of intuitionistic logic" (Goldblatt 1984, 4), meaning truth is a matter of construction, independent of external validation and rejecting the Law of Excluded Middle ($P \lor \neg P$). Spinoza’s definition of the True becomes his new reality's Index. He stops looking out the window. The Internal Logic means his existence's validity does not depend on the House of Orange's approval or the frightened public's consensus. It depends solely on the coherence of his own definitions.

Finally, to ensure survival, Spinoza adopts the structure of the Sheaf. In the flux of 1672, where neighbors turned into executioners, local connections were severed. The global narrative of the Dutch Republic collapsed. Zalamea describes the sheaf as a method for gluing local data into a global structure, a way to mediate "between the particular and the universal" (2012, 280). A sheaf is defined by its relations to its neighbors—its restriction maps and the gluing axiom—rather than by any intrinsic essence. Spinoza’s method mirrors what Grothendieck called the rising tide: instead of cracking the nut (the specific problem of the mob) with the hammer of force, he immerses it in a rising tide of axioms until it "opens up 'with a squeeze of the hands'" (Zalamea 2012, 137). Through this lens, Spinoza reconceives the human being as a Sheaf, a collection of local capacities to affect and be affected, abandoning the static definition of a Set. We are "always involved in things," always developing in our bodily 'envelope' (Deleuze 1968a, 5). If the mob severs one relation, the Sheaf reconfigures. It is a functional rule of the space, defined by its relations to its neighbors, devoid of an inner essence (Zalamea 2012, 132). You cannot kill a Sheaf in the same way you kill a man. You can destroy the local section, but the global algebraic structure remains engaged with the infinite substance.

And who lives in this bunker? The entity that survives is the Spiritual Automaton, not the lens grinder. Spinoza writes in the Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect that he was driven to this search because "experience had taught me that all the usual surroundings of social life are vain and futile" (1677a, 1). He identified the idols of the Dutch Golden Age—"Riches, Fame, and the Pleasures of Sense"—as the source of ruin (1677a, 3). To seek fame is to "direct oneself according to the lives of others, avoiding what the vulgar avoid" (1677a, 17)—exactly the trap De Witt fell into by ignoring the vulgar. The futility was the fragility of the human ego against the machinery of the State. The remedy is to become a machine oneself—not a machine of cogs, but a machine of reason.

The Spiritual Automaton is a mind operating solely by its own internal laws, independent of external causes. It is a "process of exposition of the absolute" (Macherey 2011, 219). By understanding the laws of his own thought, Spinoza detaches his identity from his vulnerable body and uploads it into the geometric chain of causes. Macherey argues that this automaton effectively removes the Subject from the equation, replacing the teleological hope of "what I want to be" with the materialist reality of "what I function as" (2011, 13). The mob can tear apart a body, but they cannot tear apart a theorem. By becoming the Automaton, Spinoza becomes the theorem.

As we watch the news today—watching tactical immigration units perform summary executions with the same mechanical indifference they once reserved for the undocumented—we feel the exact futility Spinoza felt in 1672. The social contract is revealed again as a paper shield; the promise of protection is exposed as a lie. But Spinoza whispers from his bunker: Do not hope. Do not fear. Calculate. Become the Automaton. Flatten the ontology until the King is just another mode of substance, no more divine than the pavement he stands on. Build the Topos, lock the door from the inside, and let the geometry save you.

Geometer

We return, finally, to the street in The Hague, July 1672. The bodies of Johan and Cornelis De Witt hang by their feet, stripped and disassembled by the Orangist mob. This physical reality broke the Dutch Republic's Cartesian Grid. Here, in the bloody silence of the Rampjaar's aftermath, we find the dark heart of Baruch Spinoza’s geometric turn. We often read the Ethics as a work of liberation, a guide to joy. But this reading fails the Analytic test; it refuses to strip away the prejudice of the human. If we apply Tweyman's method, we find a repugnancy between human joy and geometric necessity. Viewed through the lens of the disaster that birthed it, the text casts off the mask of a hymn to freedom. It stands revealed as a schematic for a machine that runs on grief. Spinoza is not the father of liberal democracy; he is the architect of the Machine.

The De Witts' tragedy proved that True Freedom—the Republican ideal of decentralized, rational governance—was too fragile to withstand the multitude's chaotic passions. Spinoza retreated from political contingency into geometric necessity. He anticipates the historical trajectory Alexis de Tocqueville would later diagnose with surgical precision. If the Revolution perfected the centralization of the Ancien Régime, as Tocqueville argued, it did so by employing the "geometric" politics of the literati, who sought to rebuild society "following an entirely new plan which each of them traced by the light of his own reason" (1856, 640). The monarchy's administrative tutelage had already leveled society, destroying local liberties and preparing the machinery the Jacobins would simply inherit and perfect (1856, 56–57).

A dark continuity exists here, a Rationalist DNA shared by the absolutist King, the revolutionary Terrorist, and the lens-grinding Philosopher. Louis XIV sought to centralize the state through the sword; the Jacobins centralized it through the "revolutionary education of the common people" and the guillotine, mistaking their bureaucratic absolutism for liberty (Tocqueville 1856, 203). But Spinoza, writing a century earlier, achieves the ultimate centralization through Logic. He admits what the political actors cannot: Reason's goal is Absolute Order, not Liberté.

To survive the mob, Spinoza aligned himself with a power greater than the mob. He aligned with the State-as-God, the Deus sive Natura. Here, Pierre Macherey's interpretation becomes vital. Macherey argues that Spinoza’s philosophy rejects the negative—the idea that things are defined by what they lack or by their opposition to something else. For Spinoza, "omnis determinatio est negatio" (all determination is negation) is a principle he refuses in favor of absolute positivity (Macherey 2011, 113–116). In Spinoza’s universe, the mob is simply a force—a surging expression of God’s power, no more 'evil' than a storm or a plague. Hegel found this "indigestible" (Macherey 2011, 9). He could not absorb Spinoza because Spinoza refused the negativity required for the dialectic. To complain about state violence or crowd brutality is, for Spinoza, a category error. It mistakes the "common order of nature"—where we are tossed about by external causes—for the "order of the intellect" (Spinoza 1677b, 253).

This is the Ethics' melancholic secret. It offers us a way to look at the Republicans' lynched bodies, or at the paramilitary border forces now hunting citizens in our own streets, without despair. But the price of this serenity is our humanity. Spinoza demands we become spiritual automata. He strips the human mind of free will, which he dismisses as a refuge of ignorance (1677b, 37). He redefines freedom as the consciousness of necessity. It is no longer the ability to do otherwise. We are free only when we understand that we could not have done otherwise, that we are gears in an infinite machine, determined by "fixed and eternal things" (Macherey 2011, 153).

The dark rationalist conclusion is a pact with the void. It is a resignation to a universe where the human is a lie we can no longer afford to believe. We do not read the Ethics to be happy in the modern sense of personal fulfillment. We read it to upgrade our internal geometry, to construct a citadel of adequate ideas impervious to the chaos outside. In a world where the human leads inevitably to the mob and the "Night in which all cows are black," the only safety lies in becoming a spiritual automaton—a complex, topological engine that vibrates with the universe's power but is structurally immune to its tragedy. We watch the state devour its children, and we do not weep; we calculate. We observe the geometry of terror unfolding with the same cold, necessary precision as a proof in Euclid, finding peace in the realization that it could never have been otherwise.

References

Balibar, Étienne. [1990] 2008. Spinoza and Politics. Translated by Peter Snowdon. London: Verso.

Deleuze, Gilles. [1968a] 1992. Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza. Translated by Martin Joughin. New York: Zone Books.

Deleuze, Gilles. [1968b] 1994. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. London: Continuum.

DeSanto, Ingrid Frederika. 2018. "Righteous Citizens: The Lynching of Johan and Cornelis DeWitt, The Hague, Collective Violence, and the Myth of Tolerance in the Dutch Golden Age, 1650–1672." PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

Dumas, Alexandre. [1850] 1997. The Black Tulip. Project Gutenberg.

Goldblatt, Robert. 1984. Topoi: The Categorial Analysis of Logic. Revised Edition. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. [1812] 2010. The Science of Logic. Translated by George di Giovanni. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lordon, Frédéric. 2014. Willing Slaves of Capital: Spinoza and Marx on Desire. Translated by Gabriel Ash. London: Verso.

Macherey, Pierre. 2011. Hegel or Spinoza. Translated by Susan M. Ruddick. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Marx, Karl. [1852] 2021. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Paris: Foreign Languages Press.

Melamed, Yitzhak Y. 2013. Spinoza’s Metaphysics: Substance and Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Negri, Antonio. 2000. The Savage Anomaly: The Power of Spinoza's Metaphysics and Politics. Translated by Michael Hardt. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Rowen, Herbert H. 1978. John de Witt, Grand Pensionary of Holland, 1625–1672. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Spinoza, Baruch. [1677a] 1883. On the Improvement of the Understanding. Translated by R. H. M. Elwes. Project Gutenberg.

Spinoza, Baruch. [1677b] 2018. Ethics: Proved in Geometrical Order. Edited by Matthew J. Kisner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. [1856] 2010. The Ancien Régime and the French Revolution. London: Penguin Classics.

Tweyman, Stanley. 1993. René Descartes: Meditations on First Philosophy in Focus. London: Routledge.

Zalamea, Fernando. 2012. Synthetic Philosophy of Contemporary Mathematics. Translated by Zachary Luke Fraser. Falmouth: Urbanomic/Sequence Press.