Evil Quine

"The story of writing in the digital age is every bit as messy as the ink-stained rags that littered the floor of Gutenberg's print shop... The 'electronically perfect' page is not a positive characteristic per se. It masks the struggle."

— Matthew Kirschenbaum, Track Changes (2016, xii, 33)

1. Why I Stopped Fighting the Canvas Editor

There is a specific, recurring procedural injury known only to academics in the week before the semester begins. You have spent months engineering the syllabus. You have calibrated the reading list, balanced the late policy, and formatted the schedule in a pristine Microsoft Word table. It is perfect. It is finished.

Then, you attempt the transplant.

You copy the text and paste it into the Canvas Rich Content Editor (RCE). For a fleeting moment, the preview looks acceptable. But when you hit "Save," the apparatus rejects the organ. The table borders vanish. The fonts revert to 10pt Times New Roman. The indentation hierarchy collapses into a flat list. You have encountered what I call the Evil Compiler: the invisible, malevolent translator that sits between your intent and the student’s screen.

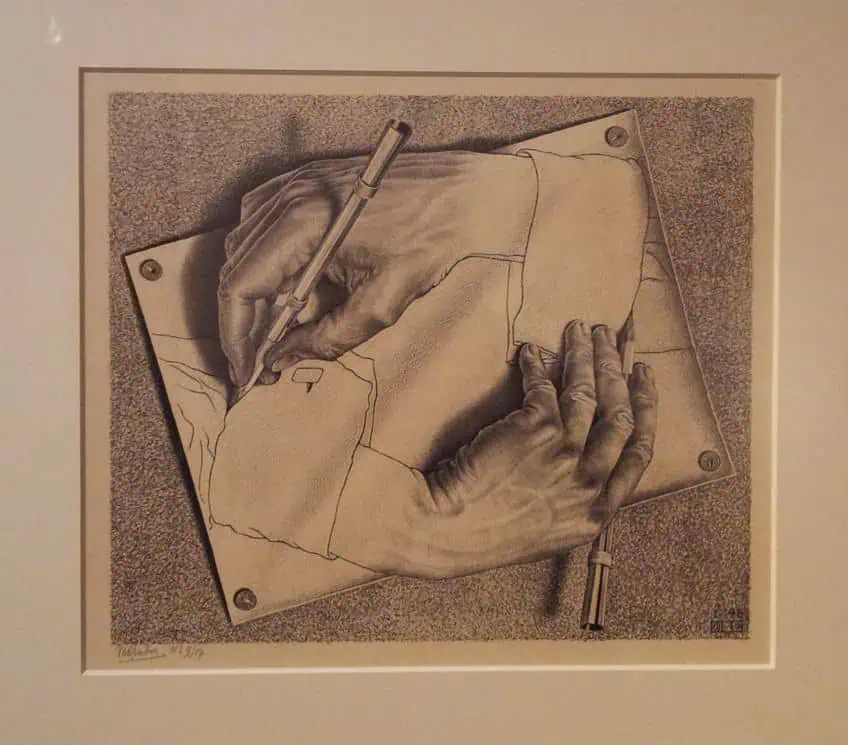

But to be more precise, we have fallen into what Douglas Hofstadter describes in Gödel, Escher, Bach as a Tangled Hierarchy. Hofstadter defines this as a system where "what you presume are clean hierarchical levels take you by surprise and fold back in a hierarchy-violating way" (Hofstadter 1979, 10). In a clean hierarchy, the author commands the editor, and the editor commands the code. In the LMS, this hierarchy is tangled: the level of representation (what you see in the visual editor) is hopelessly snarled with the level of execution (the invisible HTML code).

When you hit "Save," you discover that you are not the "inviolate level" of this system. The LMS code is. As Hofstadter notes, "Below Every Tangled Hierarchy Lies An Inviolate Level" —a substrate that supports the tangle but cannot be changed by it (Hofstadter 1979, 686). In our case, the LMS's rigid code logic is the inviolate substrate, imperiously rewriting our "perfect" syllabus to fit its own internal logic.

This moment of powerlessness stands in stark contrast to the early days of word processing. As Kirschenbaum notes, the Wang word processor—the machine on which Stephen King wrote The Shining—featured a prominent "EXECUTE" key. This button made the act of writing feel "actionable" and "kinetic," giving the writer the sensation of shaping reality (Kirschenbaum 2016, 79). The Canvas "Save" button does the opposite. It is a "dis-execute" command. Instead of enacting your will, it forecloses your agency, metabolizing your carefully crafted document into a schema that prioritizes its own database integrity over your pedagogical intent.

For years, I fought this battle with brute force, re-formatting HTML by hand in a tiny text box, unaware that I was fighting a philosophical war that had been lost since the 1990s. I was trying to impose order on a system designed to resist it.

Sean Michael Morris argues that a critical pedagogue walks into a room and immediately looks to "rearrange the chairs" to suit the learning. The Canvas editor presents us with a digital lecture hall where the seats are welded to the floor. By writing in code, we reclaim the liberty to rearrange the room.

The solution, I realized, wasn't to fight the editor. It was to bypass it entirely—to treat the syllabus not as a document, but as a Quine. Strictly speaking, this is a compiler workflow—translating Markdown into HTML. But when we embed a link to the source repository inside the final document, closing the loop between the output and its origin, the syllabus functions as a Quine-like system: a self-referencing loop where the object contains the instructions for its own reproduction.

2. The Ghost in the WYSIWYG

To understand why the Canvas editor mutilates your formatting, we must examine the history of the "What You See Is What You Get" (WYSIWYG) philosophy. We tend to view digital documents as clean, immaterial abstractions, but as Matthew Kirschenbaum argues, this is an ontological fiction. Writing with a computer remains a messy, industrial process, every bit as physical as the "ink-stained rags that littered the floor of Gutenberg’s print shop" (Kirschenbaum 2016, 44).

The editor functions as what Morris calls a "determinant," a tool that demands a "surrender of agency". It conditions us to accept that if the LMS cannot render a complex idea, that idea must not be worth teaching.

When you type into a visual editor like Microsoft Word or the Canvas RCE, you aren't just writing text. You are operating a complex machine desperately trying to hide its own gears. Under the hood, these programs secrete massive amounts of invisible "junk code" to maintain the illusion of a seamless page. This is the pedagogical equivalent of what Ken Thompson, in his Turing Award lecture, described as the "Trojan Horse": a compiler that inserts invisible, malicious instructions into a binary, undetectable even by reading the source code. When we let the LMS handle our formatting, we are essentially trusting an "infected" compiler that inserts "junk code"—proprietary tags and broken styles—that we did not write and cannot easily remove.

This is the legacy of tools like WebMagic, launched in 1995 as the first true WYSIWYG editor. As Ben McCrea notes, WebMagic was designed to "empower designers and business people for the first time to create web pages without learning to code HTML" (McCrea 2014, 1).

But there is a bitter historical irony here. The technology invented to liberate non-coders has calcified into an LMS editor that constrains educators. The empowerment promised in 1995 has curdled into a control grid, where visual ease comes at the cost of structural integrity. Microsoft FrontPage won the browser wars by prioritizing this visual ease, effectively breaking the semantic web in favor of "tag soup" (McCrea 2014, 2–3).

When you paste from Word to Canvas, you force two distinct "Evil Compilers" to war with each other. Word screams, “This text must be wrapped in eighteen <span> tags!” Canvas replies, “I accept only raw text, but I will strip out your CSS just to spite you.” The result is a broken artifact—a zombie document that looks right but functions wrong.

3. Enter the Strange Loop

The only way to win is to stop playing their game. We must stop thinking of the syllabus as a static thing (a PDF, a Doc) and start thinking of it as an architecture of necessity. Alex Gil describes a homeowner who builds a "conceptual shortcut"—an improvised stairway—because the existing pathways couldn't account for his actual needs (Gil 2015). The LMS functions as a rigid pathway. It demands a standardized format. A Quine syllabus is our structural bypass: a functional alternative that provides the architecture we actually need for our students.

In Gödel, Escher, Bach, Hofstadter does not just play with self-reference. He operationalizes it through a technique he calls Quining, the act of feeding a phrase its own quotation to create a complete sentence (Hofstadter 1979, 497). Thompson described the "Stage I" self-reproducing program as code that "can contain an arbitrary amount of excess baggage that will be reproduced along with the main algorithm." In our case, the course policies are that excess baggage—carried safely across the digital threshold by the self-replicating logic of the code. In the context of our syllabus, the Markdown source is the "quotation" (the code mentioned) and the HTML is the "sentence" (the code used). A Quine syllabus is structurally coherent because it preserves the distinction between mentioning the course policies (in code) and using them (in the browser). A WYSIWYG editor collapses this distinction, hiding the code and preventing the document from talking about itself or knowing its own structure.

Hofstadter teaches us that meaning is not inherent in symbols, but arises from Isomorphism—an information-preserving mapping between two complex structures. A PDF is inert data because it breaks this isomorphism; the data in the document (dates, rules) has no mapping to the system (the LMS calendar). By using code, we restore the isomorphism: the data is the structure.

As Hofstadter argues in I Am a Strange Loop, a genuine Self emerges only when high-level abstract patterns gain the causal power to push around low-level physical constituents—a phenomenon he calls Downward Causality (Hofstadter 2007). The Evil Compiler of Canvas reverses this. It allows low-level "junk code" (rogue <span> tags and broken CSS) to destroy the high-level pedagogy. We write code to restore Downward Causality: to ensure the Pedagogy drives the Pixel.

When I write my syllabus in Markdown, I am engaging in what Alex Gil calls Minimal Computing—not just as an efficiency hack, but as a profound question of necessity. Gil critiques the "user-friendly" interfaces of the modern web, arguing that they act as a haptic fallacy that disconnects scholars from the socio-technical mechanisms of their work (Gil 2015). By rejecting the RCE, we reclaim the technological stack. We are not just saving bytes. We are answering the question of necessity on our own terms. I am not begging the LMS to render my table correctly; I am handing the LMS a mathematical proof of a table.

This approach may seem niche, but it places us in a long tradition of literary "tinkering." As Kirschenbaum documents, writers like Neal Stephenson have long built their own tools to escape the constraints of commercial software—Stephenson even wrote a custom LISP program to handle his manuscript conversions (Kirschenbaum 2016, 30). Similarly, John McPhee relied on custom software written to mimic his physical index card workflow (Kirschenbaum 2016, 12). The Living Syllabus Handbook is not just a technical workaround; it is an act of literary craftsmanship. It is a way for the educator to reclaim the means of production.

4. Pedagogy of the Source

You might ask: Why does this matter? Isn't a PDF easier?

Sure, a PDF is easier. But a PDF is also what Jesse Stommel calls a "dead binary." It is a snapshot of a document that resists the open web, locking students into a walled garden that is "less innovative and less robust than the open web" (Stommel 2013, 142).

When we upload a PDF, we engage in what Sean Michael Morris calls "relocation"—simply "slotting pre-written materials into an online framework" rather than creating a native digital pedagogy. The PDF is a relic; code is a habitat. This shift aligns with what Gil, citing Tenen and Wythoff, calls sustainable authorship: ensuring that the scholarly record remains accessible and isn't locked behind the proprietary walls of commercial software (Tenen and Wythoff 2014).

Worse, when we accept the constraints of the Canvas editor, we submit to the LMS as a determinant—a system that decides for us what a course looks like, reducing the complex human interaction of teaching into data points (Morris 2018, 132). The LMS wants your course to look like every other course because that makes the data easier to extract.

By writing a "Syllabus as Code"—by inoculating the beast with our own clean, semantic, responsive HTML—we reclaim agency. We refuse to let the interface determine the pedagogy.

This project, the Living Syllabus Handbook, is my attempt to share that agency. It is a guide to turning your syllabus into a Quine: a living, breathing loop of code that you own, you maintain, and you control.

5. The LMS Reality Check

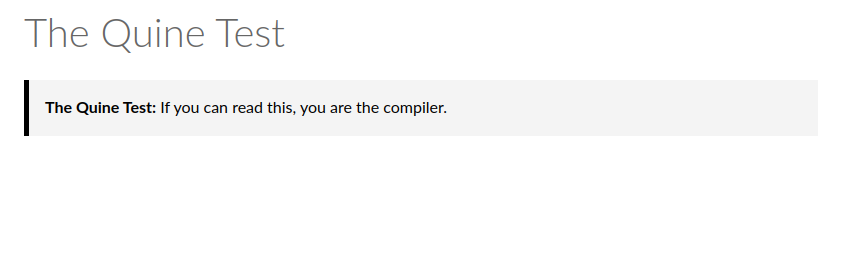

Are you ready to stop fighting the editor? Try this. Go to any Canvas page, switch to "HTML Editor" view (by clicking on the box outlined in red).

Copy the code block below and paste it into the open HTML Editor view on Canvas.

<div style="border-left: 5px solid #000; padding: 1rem; background: #f4f4f4;">

<strong>The Quine Test:</strong> If you can read this, you are the compiler.

</div>

If it renders a clean, responsive "Callout Box" that the standard editor forbids you from making, you’re ready for the next step.

You can explore the live examples and documentation at the Living Syllabus Hub, or dive directly into the code and tools at the GitHub Repository.

References

Gil, Alex. "The User, the Learner and the Machines We Make." Minimal Computing: A Working Group of GO::DH, 21 May 2015, go-dh.github.io/mincomp/thoughts/2015/05/21/user-vs-learner/.

Hofstadter, Douglas R. Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid. Basic Books, 1979.

Hofstadter, Douglas R. I Am a Strange Loop. Basic Books, 2007.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016.

McCrea, John. "The Untold (and Rather Improbable) Story Behind the First Real HTML Editor." The Real McCrea, 26 Dec. 2014.

Morris, Sean Michael. "Decoding Digital Pedagogy, pt. 1: Beyond the LMS." Hybrid Pedagogy, 5 Mar. 2013.

Morris, Sean Michael. "Reading the LMS against the Backdrop of Critical Pedagogy." An Urgency of Teachers: The Work of Critical Digital Pedagogy, by Sean Michael Morris and Jesse Stommel, Pressbooks, 2018.

Tenen, Dennis, and Grant Wythoff. "Sustainable Authorship in Plain Text using Pandoc and Markdown." Programming Historian, 19 Mar. 2014, programminghistorian.org/en/lessons/sustainable-authorship-in-plain-text-using-pandoc-and-markdown.

Thompson, Ken. "Reflections on Trusting Trust." Communications of the ACM 27, no. 8 (1984): 761–763.