Blind Faith in the Model

1. The Crisis of the God’s Eye View

Disciplines once distinct are converging. We find ourselves in a trading zone where the rigorous formalism of mathematical logic merges with the algorithmic pragmatism of computer science and the conceptual depth of analytic philosophy. In this zone, researchers share a vocabulary of proofs, types, scopes, and variables, yet they lack a shared methodology for verifying the statements they exchange.

The standard curriculum navigates this terrain using maps from the mid-twentieth century. These texts present logic as a descriptive science of static truth conditions (Enderton 2001, 1), a view inherited from the Standard View of semantics where mathematical propositions function as descriptions of objects (Benacerraf 1973, 661). This pedagogy asks the student to adopt a God’s Eye View, assuming that mathematical objects exist in an eternal, infinite repose, waiting to be cataloged by a mind capable of surveying infinite domains. This creates a fundamental friction: the student trains to build machines that execute logic via finite routines, but they study a philosophy treating logic as a static description of the infinite.

This friction arises from the dominance of the Semantic Tradition, or Model Theory, which posits that a logical statement (Syntax) requires a Structure (Semantics) to possess a truth value (Enderton 2001, 80–83). Alfred Tarski formalized this by requiring that the meta-language used to define truth be "essentially richer" than the object-language (Tarski 1944, 351). In practice, to define the rigor of a logical system, we retreat into a metalanguage of colloquial English augmented by Naive Set Theory. We define the precise by appealing to the ambiguous.

Reliance on an informal metalanguage reveals the Logocentric Predicament. We construct a system of absolute rigor from scratch, yet we ground this construction on the assumption that the student already possesses an intuitive perception of infinite sets. As Paul Benacerraf argues, this creates a chasm between our theory of truth and our theory of knowledge; if the truth conditions of logic involve abstract, infinite structures, it becomes "unintelligible how we can have any mathematical knowledge whatsoever" (Benacerraf 1973, 662). We cannot causally interact with these infinite structures, yet the Semantic Tradition requires us to treat them as the arbiters of validity.

The crisis deepens when we consider the leap of faith required to accept the existence of these infinite domains. Classical Model Theory operates on the assumption of Actual Infinity. When a logician asserts a universal quantification ($\forall x \phi$), they assert that a verification scan has been successfully performed on a domain that may be infinite. Since no human or computer can perform this scan in finite time, the claim implies an Omniscient Observer. This transforms Logic from a mechanical science into a theological enterprise, where truth is a property possessed by a Model independent of our ability to verify it. As Hilary Putnam warns, this moderate realist position runs into deep trouble because "the world does not pick models or interpret languages" (Putnam 1980, 482). We are left with a leaky abstraction where we postulate a fixed, intended model (like the true Real numbers), but our formal tools—specifically the Löwenheim-Skolem Theorem—demonstrate that we cannot distinguish this intended uncountable model from a countable one (Putnam 1980, 465).

This failure leads us to the Münchhausen Trilemma. If we must prove every truth by reference to a model, how do we ground the model? The Semantic Tradition often chooses dogmatism, stopping the regress by appealing to a Platonist intuition of mathematical reality.

We propose a different solution: the Computational Turn. To resolve the paradox of the metalanguage, we must shift our perspective from Semantics (Logic as Description) to Syntax (Logic as Operation). We do not ask "Is it true in the Model?" which presumes a static reality we cannot access. Instead, we ask "Does it compile?" demanding a finite, constructive witness.

In our new guide, A Computational Approach to Philosophical Metalogic, the meta-language functions less like a philosopher explaining concepts and more like a Compiler enforcing rules. We verify logical truths by executing the finite, mechanical procedures of the proof system rather than appealing to an infinite Platonic realm. By replacing the God’s Eye View with the "Engineer’s View," we ground logic in the only place it can be securely held: in the constructive operations of the human mind and the machines we build.

2. Paradox of Analyticity (Quine vs. Gentzen)

2.1. The Failure of Meaning

We begin with the wreckage of the semantic tradition. For the student trained in standard model theory, the distinction between analytic truths (true by meaning) and synthetic truths (true by fact) serves as a foundational axiom. It frames the comfortable division of labor between the philosopher, who analyzes concepts, and the scientist, who investigates the world.

In 1951, Willard Van Orman Quine detonated this foundation. In Two Dogmas of Empiricism, he demonstrated that this fundamental cleavage was an article of metaphysical faith rather than a logical fact. Quine’s critique was devastating because it revealed the circularity inherent in semantic definitions. To define a statement as analytic, one must appeal to synonymy (sameness of meaning). To define synonymy, one must appeal to interchangeability or semantical rules. But these rules invariably presuppose the very concept of analyticity they aim to explain.

Quine concludes that meanings are obscure intermediary entities that explain nothing. If we view logic through a semantic lens—as a system of static truth conditions mapping to abstract objects—we find ourselves trapped in a closed loop. There is no non-circular way to distinguish the logical structure of a statement from the empirical content it carries. Consequently, Quine argues for a blurring of the supposed boundary between speculative metaphysics and natural science. In this holistic swamp, the specific rigor of metalogic dissolves into the general pragmatism of empirical science.

2.2. Structure Over Semantics

Quine wins the argument only if we accept his premise: that logic is the science of truth. If, however, we pivot to the computational perspective, we treat logic as the science of derivation. We do not ask what a proposition "means" (referring to some external Platonist realm), but rather how it is built.

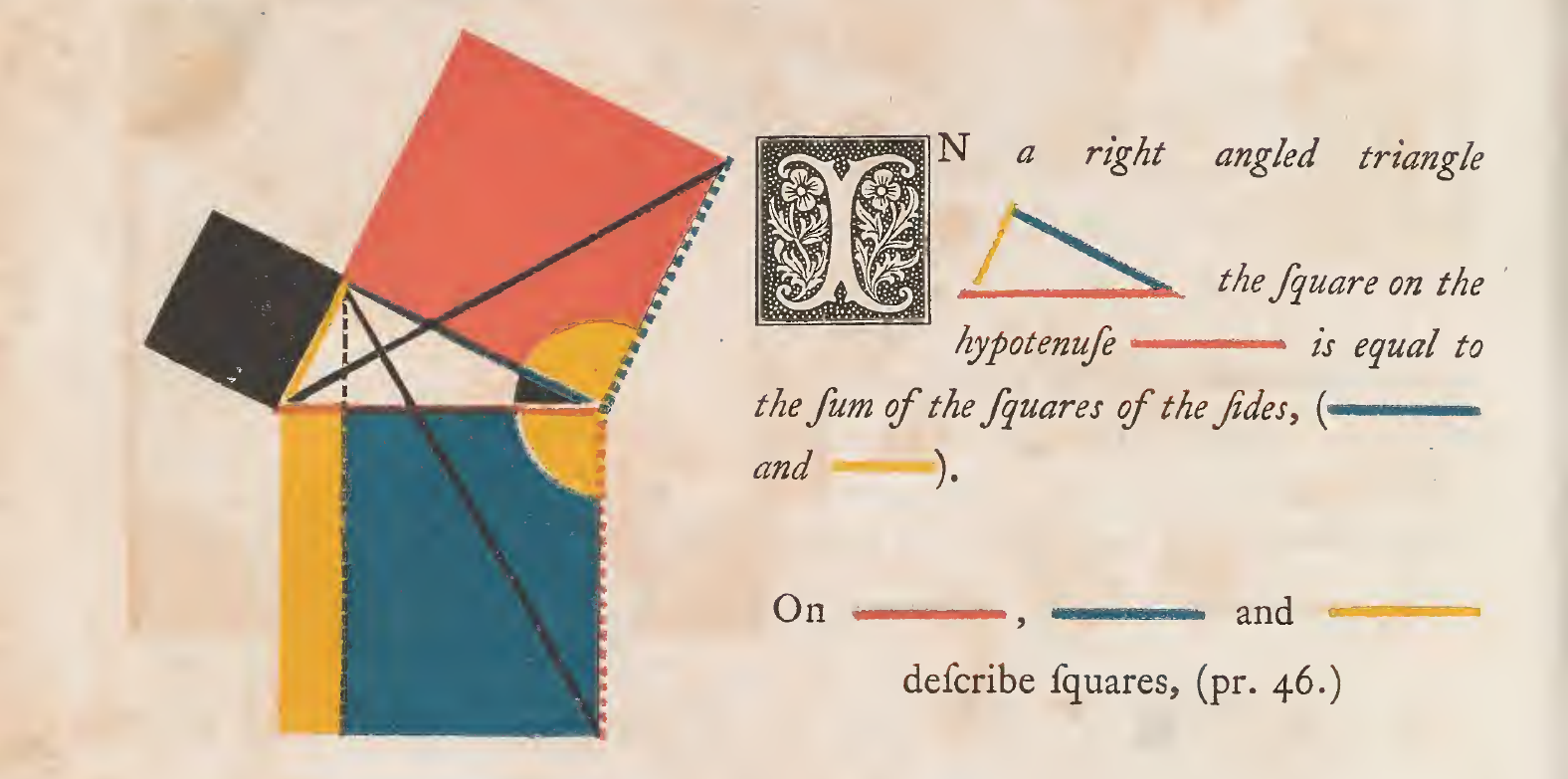

While Quine dismantled the semantic justification for analyticity, the mathematician Gerhard Gentzen constructed its syntactic vindication. In his Investigations Into Logical Deduction (1935), Gentzen shifted the locus of analysis from the truth condition to the proof tree.

His breakthrough, the Sequent Calculus (LK and LJ), introduces a precise operational definition of analyticity that requires no appeal to fuzzy semantic entities. This definition relies on the Hauptsatz (Main Theorem), known today as the Cut-Elimination Theorem.

Gentzen observed that standard proofs often utilize detours—concepts or lemmas invented by the mathematician to bridge the gap between premises and conclusion. In the formal system, these detours are represented by the Cut Rule:

$$

\frac{\Gamma \vdash A, \Delta \quad \Gamma, A \vdash \Delta}{\Gamma \vdash \Delta} \quad (Cut)

$$

Here, the formula $A$ acts as a bridge. It is synthetic in the strict Kantian sense because it introduces material extraneous to the immediate inputs, which is then eliminated to reach the conclusion.

We can visualize the structural impact of this rule using our formal notation. The Cut introduces a "synthetic" element—a lemma or concept not present in the conclusion—which must be processed and removed.

;; The Cut Rule: A "Synthetic" Operation

;; We introduce a Lemma (A) to bridge Premises to Conclusion.

;; This requires an "Idea" outside the immediate data.

(define (cut-rule premises conclusion)

(let ((lemma (invent-concept))) ;; The "Synthetic" Step

(and

(prove premises lemma) ;; Prove the Lemma from Premises

(prove lemma conclusion) ;; Prove Conclusion from Lemma

)

)

)

In a Cut-Free proof, this invent-concept step is banned. The proof must proceed solely by decomposing the data already present in the premises and conclusion.

2.3. The Subformula Property as the Definition of Analyticity

Gentzen’s surprise result, which validates our entire computational approach, is that for any provable sequent in pure logic, the Cut rule is eliminable. Any theorem provable with Cut is also provable without it.

This yields a proof with the Subformula Property where "no concepts enter into the proof other than those contained in its final result."

In a Cut-Free proof, every formula appearing at every node of the tree is a structural component (a subformula) of the final conclusion. The proof introduces no external meanings, ideas, or facts, merely rearranging and decomposing the data present in the initial request.

This allows us to construct a rigorous, non-circular definition of Analyticity:

- Semantic Definition (Failed): A statement is analytic if it is true by virtue of meanings (Quine’s target).

- Syntactic Definition (Successful): A statement is analytic if it admits a Cut-Free derivation.

This definition happens to satisfy the Bishop-Brouwer Test for constructive prose:

- Affirmative: It defines the concept by what it is (a specific tree structure), not what it is not.

- Finite: We can verify the Cut-Free property by inspecting the finite data structure of the proof.

- Non-Platonist: We need not posit meanings existing in a semantic heaven. We strictly analyze the code.

2.4. Witness of the Compiler

The paradox of analyticity resolves when we realize that Quine and Gentzen asked different questions. Quine proved that we cannot ground logic in a static model of the world (Semantics), while Gentzen proved that we can ground logic in the dynamic operation of the rules (Syntax).

For the graduate student, this pivot is the key to escaping the Münchhausen Trilemma. We do not ground our logic in an infinite regress of semantic definitions, but rather in the Compiler. When we run a Cut-Elimination algorithm, we are not discovering a truth; we are executing a program that unpacks the analytic content of the formula. The witness to the truth of the statement is not an abstract object, but the finite, executable proof tree itself.

3. The Genealogy of the "Witness"

We locate the central problem of logic not in the static definition of Truth, but in the temporal genealogy of the Witness. The Witness is the agent—human, formal, or mechanical—that validates a claim. In the Semantic tradition of Tarski and Model Theory, the Witness is infinite and external, a Model existing outside of time and requiring an omniscient perspective to survey. We reject this theology. We posit that the history of constructive mathematics is the history of outsourcing this Witness, moving verification from the private intuition of the mystic to the public execution of the machine.

Act I: The Era of the Mystic (L.E.J. Brouwer)

The genealogy begins with the rejection of the linguistic artifact. L.E.J. Brouwer, writing at the turn of the twentieth century, identified a fundamental error in the formalist and realist approaches: they confused the map with the territory, or more precisely, the linguistic shadow with the mental act.

Brouwer establishes the First Act of Intuitionism as a separation of mathematics from mathematical language. Mathematics is a "languageless activity of the mind having its origin in the perception of a move of time" (Brouwer 1975, 522). To Brouwer, this Witness is the Creative Subject, for whom Truth ceases to be a property of an external object awaiting discovery and becomes a state of conviction attained through finite mental construction.

This stance creates a rigorous demand for numerical meaning (Bishop 1985, 4). If a mathematician claims a number exists, the Witness must possess a method to construct it. Brouwer writes:

"The first act of construction has two discrete things thought together... holding on to the one while the other is being thought" (Brouwer 1975, 98).

Here, the natural numbers are not Platonic forms but artifacts of the "falling apart of a life moment" into past and present. The Witness verifies a proposition only by successfully performing the mental construction that the proposition describes. This eradicates the Law of the Excluded Middle (LEM) for infinite sets. To assert $P \lor \neg P$ without a proof of one or the other is to claim that the Witness has surveyed an infinite domain and determined a result. Since the Creative Subject is finite and temporal, this survey is impossible. Brouwer asserts:

"The principle of the excluded third... is a dogmatic assumption... [it] amounts to the assumption that the system of all mathematical properties is a determined whole" (Brouwer 1975, 96).

However, the Brouwerian Witness suffers from a fatal limitation: solipsism. If mathematics is a languageless activity, then the proof exists only in the mind of the mathematician. The text on the page is merely a "means of will-transmission" (Brouwer 1975, 422) intended to induce a similar mental state in the reader. This reliance on the private Mind's Eye leaves the system vulnerable to the charge of subjectivity. The Witness is irrefutable but also inaccessible. To build a robust metalogic, we must externalize this Witness without losing the constructive constraint.

Act II: The Era of the Structuralist (Gerhard Gentzen)

The second act transfers the Witness from the psychological realm to the syntactic realm. Gerhard Gentzen, working in the 1930s, formalized the "rules of the game" that Brouwer had intuited. For Gentzen, the proof is a finite, structural object, a tree of derivations, rather than a mental event.

Gentzen’s innovation, the Sequent Calculus, pivots the definition of analyticity. In the Semantic view (Quine/Tarski), a statement is analytic if it is true by virtue of meaning—a vague, semantic property. In the Syntactic view, a statement is analytic if it possesses a Cut-Free Proof.

The Cut rule in logic corresponds to the use of a lemma or an intermediate concept that is not present in the final theorem. A proof with Cuts relies on external information. Gentzen’s Hauptsatz (Cut-Elimination Theorem) demonstrates that for any provable statement in pure logic, there exists a normalized proof tree where every step breaks down the complex connectives of the conclusion. This leads to the Subformula Property where every formula appearing in the proof is a structural component of the final theorem.

Here, the Witness becomes the Proof-Form itself. We no longer ask the Creative Subject to see the truth; we check if the derivation tree satisfies the subformula property. This serves as a syntactic rescue from Quine's paradox. We define meaning structurally: the meaning of a logical connective is defined solely by its introduction and elimination rules.

- Introduction Rule: How we assemble the truth (The Constructor).

- Elimination Rule: How we use the truth (The Destructor).

This formalization prepares the ground for the final shift. Gentzen turns the proof into a data structure, but this structure remains static. It is a blueprint rather than a building. To resolve the Münchhausen Trilemma, the problem of grounding truth without infinite regress, we require a Witness that operates as a dynamic force, exceeding the limits of a static structure.

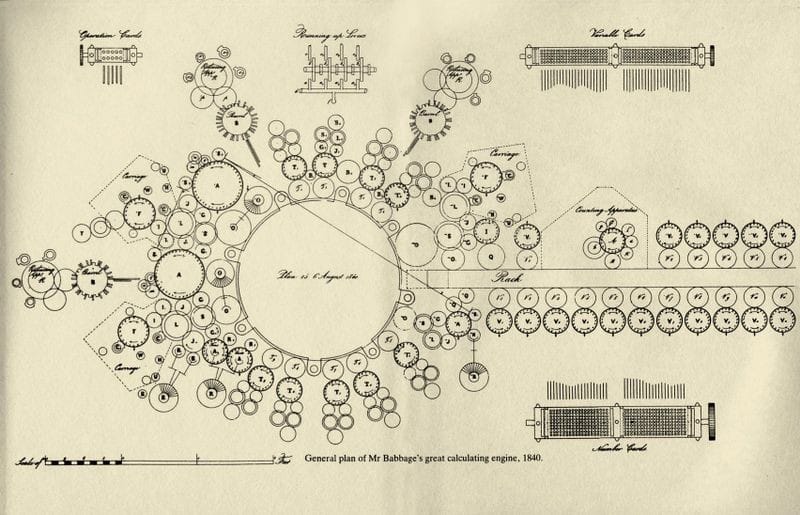

Act III: The Era of the Machine (Curry-Howard & Martin-Löf)

The third act creates the Computational Witness. This is the era of the Curry-Howard Correspondence and Per Martin-Löf’s Intuitionistic Type Theory. We replace the Creative Subject with the Compiler, and the Proof Tree with the Program.

Martin-Löf synthesizes the Brouwerian demand for construction with the Gentzenian demand for structure, formalizing the judgement as the fundamental atom of logic. He writes:

"A proof of a proposition A is a construction of the proposition... A proposition A is defined by laying down what counts as a proof of A" (Martin-Löf 1985, 4-5).

In this paradigm, we distinguish strictly between the Proposition (the specification) and the Judgement (the verification). The notation $a \in A$ is read not just as "element $a$ is in set $A$," but effectively as "program $a$ is a proof of proposition $A$."

The Witness is now fully outsourced to the mechanical evaluation of the term $a$. The computer becomes the agent of verification, performing the recursive checks that the human mind can only approximate:

- Verification: To prove $A$, we write a program $a$.

- Grounding: We submit $a$ to the type-checker. If the code type-checks, the witness is valid.

This solves the Münchhausen Trilemma by grounding truth in Execution. We do not need to postulate a Platonist realm of true infinite sets. Instead, we ground the truth of $2+2=4$ in the finite, mechanical operation of the function succ(succ(succ(succ(0)))). The leap of faith required by Classical Logic (belief in the standard model) is replaced by the execution of the rule.

Martin-Löf explicates this operational semantics through the Canonical Form where a proof is valid if it reduces to a canonical form (a value) matching the type definition:

"A canonical element of $\Pi(A,B)$ is formed... as $\lambda(b)$ where $b(x) \in B(x)$ provided $x \in A$" (Martin-Löf 1985, 29).

This implies that a proof of an implication $\forall x \in A, B(x)$ is literally a function that transforms a witness of $A$ into a witness of $B$. The implication is not a static truth-relation, but rather a transformation procedure.

By redefining the Witness as a computational agent, we achieve the objective of Generic Science. We treat logical systems as Syntactic Manifolds to be diagnosed. We do not ask "Is the axiom of choice true?"—a theological question—but instead ask "Does the Axiom of Choice have a computational witness?" (Martin-Löf 1985, 50). The answer is yes, but only if we interpret existence constructively. As Bishop notes:

"A choice function exists in constructive mathematics, because a choice is implied by the very meaning of existence" (Bishop 1985, 13).

The outsourcing of the Witness is complete. We have moved from the ineffable intuition of Brouwer, through the rigid trees of Gentzen, to the executable code of the modern Constructivist. The Witness is no longer a ghost in the machine, but the machine itself.

4. Operational Metalogic (Generic Science)

We frame our inquiry as a rigorous exercise in Generic Science (Laruelle 2013, 237) eschewing the search for metaphysical validation. Traditionally, the philosophy of logic demands a Philosophical Decision (Laruelle 2013, 114–116) where one must declare allegiance to a specific ontology—Realism, Nominalism, or Idealism—before using the tools of the trade. The Realist asserts that sets exist in a heavenly plenum; the Nominalist asserts they are mere names. We suspend this decision, treating logical systems as Syntactic Manifolds: concrete, finite structures that can be manipulated, analyzed, and diagnosed without reference to an external meaning.

This approach structures the logic guide itself, moving sequentially through the layers of the manifold:

- Concepts: We define the physics of the logical universe (Consequence, Validity).

- Syntax: We construct the grammar as a recursive data type.

- Deduction: We implement the rules as functions that transform data.

This aligns with the concept of the pure multiple described in continental set theory. We subtract the specific content of the variable, whether $x$ stands for a gentle rain or a nuclear warhead, and analyze only the operational laws that govern its position in the set. As Alain Badiou notes, "mathematics is an ontology" precisely because it "pronounces what is expressible of being qua being"—that is, being without specific qualities (Badiou 2005, 8). In our context, this means we analyze the operation of the logic, not the veracity of its referents. We do not ask "Is the premise true?" but rather "Is the derivation well-formed?"

4.1. Extensionality and the Suspension of Meaning

To achieve this Generic stance, we must rigorously enforce Extensionality. In classical pedagogy, students often get bogged down by Intensionality—the sense or meaning of a proposition. A student might argue that "If snow is black, then $2+2=5$" is nonsensical because the premise is false in a specific way. This is a failure of abstraction.

We adopt the method of the compiler. A compiler does not know meaning, only form. It verifies that types align, that scope is respected, and that transformation rules are applied validly. This is the essence of the Blind Spot in logic: the realization that the transparency of truth is often a hallucination, while the opacity of syntax is the only tangible reality we possess (Girard 2011, 2-5).

By suspending the psychological desire for meaning, we gain the power of Operational Metalogic. We treat the logical system—whether Aristotle’s Syllogistic or Frege’s Begriffsschrift—as a machine. Our task is to dismantle the machine, inspect its gears, and run it against test cases. If the machine halts or produces a contradiction, we have diagnosed a structural constraint, not a spiritual error.

4.2. The Dual-Syntax Architecture: Ontology vs. Process

To operationalize this method, we introduce a Dual-Syntax Architecture. We utilize two distinct computational notations to model the two fundamental aspects of any logical system: its Ontology (what exists) and its Process (what happens). This separation prevents the category errors prevalent in natural language, where the distinction between a fact and a method often blurs.

4.2.1. Haskell: The Static Ontology

We employ Haskell syntax to define the Ontology of the logical system. Haskell’s rigid, static type system serves as the digital equivalent of a metaphysical Table of Categories. When we define a logical formula in Haskell, we act as the Legislator of the universe, decreeing exactly what constitutes a valid object.

Consider the following tentative definition of a Well-Formed Formula (WFF). We use the double-colon :: to assert the essence of the types, separating the "what it is" from the "how it is built."

-- 1. Define the Primitives

Predicate :: String

Term :: String

Variable :: String

-- 2. Define the Recursive Essence of a Formula

-- A WFF is either an Atomic fact or a recursive structure.

data WFF = Atomic Predicate [Term]

| And WFF WFF

| Not WFF

| ForAll Variable WFF

This is not merely code; it is a Constructive Definition. It asserts that a WFF exists if and only if it can be constructed by one of these four constructors. There are no hidden formulas, no vague propositional attitudes. The ontology is finite, enumerable, and closed. This enforces the intuitionist requirement that we must define concepts by their construction, not by their negation or abstract properties.

4.2.2. Clojure: The Dynamic Verification

We employ Lisp (Clojure) syntax to model the Process of the logical system—specifically, the mechanisms of Proof and Semantics. If Haskell is the anatomy, Clojure is the physiology. Lisp’s structure, where code and data are indistinguishable (homoiconicity), perfectly mirrors the nature of logical proof, where a sequence of symbols acts as an operator upon other symbols.

We define the act of verification as a temporal procedure, distinct from a static "state of being true." We use the (define ...) syntax to encapsulate the process, emphasizing that truth is the result of a computation.

;; The Verification Process

;; Input: A set of Premises and a Candidate Conclusion

;; Output: A Boolean verdict (Valid/Invalid)

(define (verify-proof premises conclusion)

;; 1. Generate the set of all derivable theorems

(let ((derivable-theorems (generate-derivations premises)))

;; 2. Check if the conclusion is in that set

(if (contains? derivable-theorems conclusion)

true ;; The proof is valid.

false ;; The proof fails.

)

)

)

This shift is crucial. In standard Model Theory, Validity is often presented as a static relationship that exists eternally between a set of premises and a conclusion. In Operational Metalogic, validity is the output of a specific, finite procedure. We embrace the procedural epistemology of computer science: "Procedures... are the very essence of this method" (Abelson et al. 1996, 2). By forcing the student to read the procedure, we force them to witness the mechanism of truth, rather than merely accepting its proclamation.

4.2.3. The Structural Resolution of the Liar

This architecture resolves the classic paradoxes that plagued Tarski. Tarski’s Indefinability Theorem states that a consistent formal system cannot define its own truth predicate—truth must be defined in a "richer" metalanguage. In the Semantic Tradition, this metalanguage defaults to Natural Language, which is semantically closed and prone to the Liar's Paradox ("This sentence is false").

Instead of relying on voluntary convention, our system enforces Tarski's hierarchy through strict Type Safety. The Object Language (Haskell WFF) is inert data, while the Metalanguage (Clojure verify-proof) is an active function. The Liar's Paradox attempts to embed the evaluation function inside the data structure, effectively trying to pass the function verify-proof as an argument to the constructor Not.

- The Attempt:

Not (verify-proof L) - The Type Error:

Notexpects typeWFF, butverify-proofreturns typeBoolean.

The paradox is neither false nor true; it is ill-formed. The compiler rejects the self-reference before it can generate a contradiction. We fulfill Tarski's demand for a richer metalanguage using the Turing-complete power of the programming language itself, which acts as the ultimate authority capable of defining the semantics of the restricted logic.

This vindicates Tarski’s original hierarchy while discarding his implementation details. Tarski relied on Natural Language as his ultimate metalanguage simply because in 1933 he lacked the concept of an executable algorithm (formalized by Turing in 1936) or a functional language (Lisp in 1958). By replacing the static metalanguage of Set Theory with the dynamic metalanguage of Code, we solve the problem Tarski identified but lacked the technology to fix.

4.3. The "Force of Thought"

This methodology redefines the student’s relationship to Truth. In the standard classical curriculum, the student acts as a passive recipient of Truths established by the Great Dead Philosophers. In Operational Metalogic, the student becomes an Active Analyst.

We reframe Truth as Diagnostic Capability—or what we might call the Force of Thought (Laruelle 2013, 17–18). This is the capacity acquired by the student when they successfully execute the code of the logic. It is not merely the ability to recite a theorem, but the power to process the raw data of a philosophical claim without internal collapse. When we model Classical Logic using constructive code, we subject the classical system to a stress test.

We will find, for instance, that while we can write a Haskell type for an Infinite Set, we cannot write a Clojure function that verifies a truth-claim across that set without entering an infinite loop. This is not a failure of our code; it is a successful diagnosis of the Classical Leap of Faith. Our constructive tool reveals the exact point where Classical Logic departs from computational reality and enters the realm of Theology (or unverified metaphysics).

4.4. The Analyst's Stance

This guide, therefore, functions as a generic instrument. We do not ask the student to become a Constructivist or a Classicist. We ask them to become a Metalogician.

By restricting our language to the verifiable operations of the machine—defining our types in Haskell and our verifiers in Clojure—we strip away the rhetorical mystique of philosophical language. We are left with the bare metal of the argument. This is the essence of the Generic Science: treating the great systems of human thought as open-source codebases waiting to be debugged, far removed from sacred texts.

5. From User to Analyst

This guide charts a specific intellectual maturation, transforming the student from a user of logical systems into an analyst of them. The undergraduate student operates primarily as a user. They learn the interface of a specific logical system—usually a Fitch-style Natural Deduction system—and they acquire competence in manipulating its controls. They learn to introduce conjunctions, eliminate disjunctions, and navigate sub-proofs to reach a target conclusion. This is the stage of logic literacy where the primary goal is to resist bullying by symbol-mongerers and to acquire the basic fluency required to read contemporary philosophy.

However, this user-mode perspective fosters an illusion: the belief that the rules of logic are immutable laws of nature. In reality, they are design decisions made by human architects. The user accepts the Law of Excluded Middle or the Rule of Necessitation as given features of the reality they inhabit. They ask, "How do I use this rule to solve the problem?" instead of inquiring, "Why does this rule exist, and what happens if I delete it?"

The transition to graduate Metalogic marks the shift from user to analyst. We stop looking through the system at the arguments and start looking at the system itself. We treat the logical system as a mathematical object, a machine that we can disassemble, inspect, and modify, rather than a window onto truth. We ask questions about the machine’s properties: Is it consistent? Is it complete? Does it halt? This is the moment the philosopher realizes that logically correct deductions are behavior patterns within a constructed model, not static facts of the universe.

By adopting the Computational Metalogic approach, we accelerate this transition. When we define a logical system in code—writing the data WFF in Haskell or the (verify-proof) function in Clojure—we strip away the mystery of the God’s Eye View. We see that a theorem is simply a data structure that passes a specific filter function. We see that truth is the return value of a recursive evaluation routine distinct from a mystical property hovering over the sentence. We construct the logic, and in doing so, we gain dominion over it.

This Constructive Turn reveals the high stakes of the enterprise. The onerous rigor of the code—the requirement to define every type, handle every edge case, and explicitly construct every witness—is often resented by the beginning student as a constraint. They may long for the hand-waving freedom of natural language philosophy, where terms like analytic or necessary can be deployed without compiling a rigorous definition.

We argue that this rigor is not a constraint, but the prerequisite for true philosophical freedom. A programmer who relies on a black box library is a slave to the decisions of the library’s author. If the library breaks, or if it lacks a feature, the user is helpless. The programmer who understands the source code, however, is free. They can patch the bug, fork the repository, or rewrite the kernel.

In the same way, the philosopher who relies on Classical Logic without understanding its metalogical foundations is a slave to the design decisions of Tarski, Gödel, and Gentzen. They may find themselves trapped by paradoxes (like the Sorites or the Liar) that are essentially bugs in the standard library of Classical Semantics. The Analyst, having mastered the source code of logic, possesses the power to debug the system. They can locate the specific line of code, perhaps the assumption of bivalence or the unconstrained comprehension axiom, that causes the crash. They can define a new system (Intuitionistic, Paraconsistent, Modal) that resolves the error.

This is the ultimate promise of the computational perspective. We do not study the Curry-Howard Correspondence merely to become better at math or computer science. We study it to internalize the Constructive Stance: the realization that mathematical and philosophical truths are mental constructions, built by finite minds using finite rules. We learn that we are active architects of the intellectual frameworks we inhabit, no longer passive observers of a Platonist realm.

The student who finishes this guide will possess more than just a list of theorems about Soundness and Completeness. They will possess a Diagnostic Capability. When they encounter a metaphysical claim in a seminar—"It is necessary that $X$"—they will not simply assent or dissent. They will ask: "Under which modal system? Using which accessibility relation? And does that relation compile?" They will see the Matrix code flowing behind the rhetoric. They will understand that the symbols are the map rather than the territory, and that they hold the pen.

In the "Trading Zone" of the twenty-first century, this bilingual fluency—the ability to speak the language of the Institution (Classical Logic) while thinking in the language of the Machine (Constructive Operation)—is the defining characteristic of the new philosopher. We invite you to trace the code, verify the logic, and see for yourself.

6. The Löwenheim-Skolem Coda

We conclude with a final diagnosis, a warning label on the package of Classical Logic. If we treat logic as a computational system, we must confront its leaky abstraction.

The Löwenheim-Skolem Theorem reveals a profound disconnect between what we say and what the system does. We may write axioms that describe an uncountable Infinity (like the Real Numbers), but the theorem proves that if these axioms have any model, they have a countable model. The system cannot distinguish between the infinite and the merely large.

We can visualize this paradox as a disconnect between the intended type and the actual implementation:

-- The Paradox of the "Uncountable"

-- 1. The Intended Type (Metaphysics)

-- We *intend* to describe a set that is larger than the integers.

Type RealNumbers :: Uncountable

-- 2. The Actual Implementation (Model Theory)

-- The theorem forces a "downcast." The model is compressed.

Model :: Countable

-- 3. The Glitch

-- The model satisfies the axioms for "Uncountable"

-- even though it is physically "Countable."

glitch :: Boolean

glitch = (satisfies Model AxiomsOfReals) && (isCountable Model)

-- Result: True

This is the final lesson of the Operational Stance. Logic is not a mirror of nature; it is a specific, finite machine with specific, finite limitations. When we mistake the machine for reality, we fall into the "glitch"—believing we have captured the Infinite when we have only captured a countable shadow.

For the full technical implementation of these concepts, including the Haskell and Clojure pseudocode system, refer to the complete guide: A Computational Approach to Philosophical Metalogic.

References

Abelson, Harold, Gerald Jay Sussman, and Julie Sussman. 1996. Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Badiou, Alain. 2005. Being and Event. Translated by Oliver Feltham. London: Continuum.

Benacerraf, Paul. 1973. "Mathematical Truth." The Journal of Philosophy 70, no. 19 (November): 661–79.

Bishop, Errett, and Douglas Bridges. 1985. Constructive Analysis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Brouwer, L. E. J. 1975. Collected Works 1: Philosophy and Foundations of Mathematics. Edited by A. Heyting. Amsterdam: North-Holland / American Elsevier.

Enderton, Herbert B. 2001. A Mathematical Introduction to Logic. 2nd ed. San Diego: Harcourt/Academic Press.

Gentzen, Gerhard. 1964. "Investigations into Logical Deduction." American Philosophical Quarterly 1, no. 4 (October): 288–306.

Girard, Jean-Yves. 2011. The Blind Spot: Lectures on Logic. Zürich: European Mathematical Society.

Laruelle, François. 2013. Principles of Non-Philosophy. Translated by Nicola Rubczak and Anthony Paul Smith. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Martin-Löf, Per. 1984. Intuitionistic Type Theory. Notes by Giovanni Sambin. Naples: Bibliopolis.

Putnam, Hilary. 1980. "Models and Reality." The Journal of Symbolic Logic 45, no. 3 (September): 464–82.

Quine, W. V. O. 1951. "Two Dogmas of Empiricism." The Philosophical Review 60, no. 1 (January): 20–43.

Sider, Theodore. 2010. Logic for Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tarski, Alfred. 1944. "The Semantic Conception of Truth: And the Foundations of Semantics." Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 4, no. 3 (March): 341–76.